Matthias Muche: interview with the trombone player from Cologne

Matthias Muche studied at the Conservatory Amsterdam, at the Conservatory Rotterdam, the Musikhochschule and audiovisual media at Kunsthochschule für Medien Köln. He is a member of the Schäl Sick Brass Band, of the Multiple Joy(ce) Orchestra and of the Niels Klein Tentet. Since 2004 he cooperates with Sven Hahne as artistic director of Frischzelle - Festival für intermediale Improvisation und Komposition.

Was music a daily diet when you grew up?

MM: Yes, it was important but not very important. My parents sang in a church choir. Church music was part of the daily life.

Did your parents keep a collection of vinyl you could flick through?

MM: Yes, they had a selection of vinyl like Franz Josef Degenhardt, Wolf Biermann and a lot of Bach's cantatas, church brass music and music composed by ABBA but not Jazz at all.

Why did you start to play trombone? Trombone is not very sexy in comparison with drums, e-bass or e-guitar; specially not when you are a teenager?

MM: The main reason was Xmas in a way going to church and singing “Oh, du Fröhliche ...”. You can hear the brass choir with a high trombone voice and some timpani (kettle drums). That was quite impressive. Most of the general music performed in church was connected to the trombone choir too. That was something I was very much interested in. They started with beginners brass choirs for kids and I learned to play the trombone in such an ensemble at the age of twelve.

Did your parents support your intention to play trombone?Or was it just what you wanted to do and you did it?

MM: I wanted to play trombone and my parents liked the idea. After a while they “sponsored” some lessons at the local school of music.

Is there a special affinity between the instrument you picked to play and your personality?

MM: (with a bit of laugh) I think so. You choose your instrument because of a certain connection and ability. If I would have made another pick I would have chosen the cello. That means I would stay in the same register. I would say the trombone and I fit very well together.

Do you remember the first Jazz album or tunes you came across? How important do you regard the music you picked first for your career?

MM: I grew up in a small village close to Bielefeld and went to a comprehensive school at Bielefeld. There were a lot of music teachers and one was a Jazz enthusiast. He set up a Jazz workshop for those interested in playing Jazz. I think one of the first pieces we played was 'Hello Dolly'. (Matthias cracked up when he told me that story.) We played as well pieces like 'Equinox' (John Coltrane) and others. This particular teacher was a sort of focal point for discovering Jazz.

J. J. Johnson and Curtis Fuller are two quite important trombone players in the history of Jazz and I would like to know if those musicians influenced you? Have you been ever attracted by those musicians I mentioned?

MM: It is quite funny because J. J. Johnson is for many, many trombone players very important. In the beginning I used to listen a lot to tunes by J. J. Johnson. I heard a lot of concerts of Albert Mangelsdorff playing live in different combinations as well. I went to those concerts and was fascinated of course but I was not really connected to his way of playing in the first place. Now he is the most important trombone player for me. I think he is one of the most modern trombone performers. In the beginning it was J. J. Johnson and now Albert is my favourite trombonist.

Did you play first of all straight-ahead Jazz before entering the field of Free Jazz and free improvised music?

MM: As I stated before I played very traditional old style Jazz in the school band but as well some more modern stuff because the teacher who organised the workshop was very open minded. Improvisation was very important. When I was 16 I went every weekend to the Bunker Ulmenwall at Bielefeld. You could say that I stepped from the straight-ahead Jazz straight into the German avant-garde Jazz. I encountered Knitting Factory, the Jazzhaus and Jazzinitiative Köln.

Why is avant-garde or contemporary music so attractive and fascinating for you?Is it the freedom and space not depending on themes, bridges, changes and so on?

MM: There is more space but I would not say more freedom. Avant-garde and contemporary music have their own rules. You start to play your instrument; you start to play in bands, you start to develop the music you love and you are going on and on and on not stopping developing your personal style. Playing contemporary music is a sort of coming out and the result of a process. But there are others they develop their own style by playing straight-ahead Jazz. Everybody has the freedom to do what he wants to do.

Do you think that improvised music can be characterised as controlled loss of control?

MM: Yep.

… or is that very theoretical thinking about music and the process of performance? The question is based on a book I came across which compares the theory of Freud and the process of analysing the psyche of a person with improvised music. Can you connect to it or do you think that is total nonsense?

MM: (He had a good laugh when I explained my question!) I don't know. You can as well say random with choice. It's the same.

But there must be a sort of frame work or system for those improvising. How does it work? Somebody starts and that is followed by a reaction and so on?

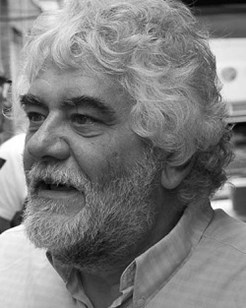

(At that point Matthias Schubert stepped in the conversation. He was due to perform with Matthias Muche in a 40 minutes improvisation later that day. Few background lines about the saxophonist Matthias Schubert: He studied between 1979 and 1983 at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg. Among his teachers were Herb Geller and Walter Norris. Schubert was part of the Euro Jazz Band, the Graham Collier Band and the Marty Cook Group. He joined the stage as well with Albert Mangelsdorff. He founded James Choice Orchestra with Carl Ludwig Hübsch, Frank Gratkowski and Norbert Stein. Since 2001 he teaches at the Hochschule für Musik, Theater und Medien Hannover.)

MS: Well, someone sets an idea. Your counterpart either follows the idea or ignores it or makes something out of it. It's like a conversation.

Is anticipation a keyword? Do you have to know what the other person has in mind to play? Does that mean you are always in alert? Is it important to know each other quite well to improvise and play free improvised music?

MM: No, but what is quite common in improvised music is a kind of blind date or that ad-hoc putting people together who never played with each other before. This could be a very interesting performance for the audience. What Matthias said a conversation when you put interesting people together on stage and they deal with each other. That could be very interesting because you don't know each other well enough. It could be as well quite horrible because you don't find a point to connect. It could be as well interesting not to be connected and to handle that. I think there is no rule. On the other hand it is very important that groups improvising together and knowing each other very well. Both forms of improvisation can be entertaining. Working together and knowing each other very well result maybe in different music. But the thrill is as well not to step into the known footprints and make the same decisions you always make.

Is it possible to learn to improvise? Is a special technique involved in improvised music? Is it naturally inbuilt? Do you have to be very talented?

MS: I think everyone can improvise. If you have the feeling you are not able to improvise is a matter of education. I think everybody has the ability to improvise but it is just buried by education. In classical music you are trying to interpret a piece, grab the music and do something with it in your own way.

MM: I agree. It always depends on the people you meet when you start making music. Of course if you meet someone who sticks to his methods how to learn it and what to do first then is difficult to open up the path for you.

My impression of improvised music has to do with anticipation and knowing what will be up next. You have to rely on each other but still develop your own ideas.

MS: That is one way but the other is to completely ignore the surroundings and my counterparts. Do I want to build a structure or don't I want it. There are many possibilities. Improvisation is like stepping out of this room and making a decision like do I go straight or make a right turn. Why do I make the right turn? Maybe I felt like going that way. Maybe someone stands there and I felt compelled to this person. In improvised music there are options where you want to go. This could be a process of consciousness or subconsciousness. Referring to improvised music as controlled loss of control I would say that a great pianist like Alfred Brendel plays notated music and whenever he plays the same pieces he is doing it in different versions. I think he makes decisions of musical expressions at the very moment. That does not so much depend on the type of music. I think it is one of the highest achievements in music and in listening to music that control is lost in a certain way to achieve a sort of 'higher spirit'.

When playing you need a beginning and an ending. How do you know when it is all over?How do you know that everything is expressed? Or do you think improvised music is a continuous process?

MM: Improvised music is happening on stage. You present your music to an audience. I like the idea of a debate or discussion. Someone has something in mind and starts to talk and the others make the connection to it. But this happens in a sort of frame. The frame today is the time set of 40 minutes. You can present a story even if it is not narrative music. Anyhow you have to deal with the frame set up and you have to make a certain statement.

MS: Either we find a common language, syntax or grammar or we don't. Staying with that picture one speaks Italian and the other German and both speak about totally different issues. You then do not get any common ground.

You recorded the CD 'Transferration' as the duo named '7000 Eichen'. A recording means there is a strict frame panel set. There is no chance to extend the length of time. How do you fit all your ideas in that frame?

MM: The CD was released together with the guitarist Nicola Hein. There are various types of CD like a live recording of a concert as a kind of documentation and like one you have thought about the format of the CD and then you play maybe different music than in a live concert. Referring to the CD 'Transferration' we were thinking of playing a type of soft chamber music on a very high energy level with a noisy vocabulary. Pieces of six to eight or nine minutes were the results. That worked out very well.

I would like to quote John Coltrane: 'Over all, I think the main thing a musician would like to do is give a picture to the listener of the many wonderful things that he knows of and senses in the universe. That’s what I would like to do. I think that’s one of the greatest things you can do in life and we all try to do it in some way. The musician’s is through his music.' Do you share Coltrane's view?

MM: Sounds good (a laugh!). Of course you deal with energy and there are situations in which control is given away. Yes, it is about dealing with constructive energy given to the world. As an artist and musician that is a goal you want to achieve.

Thanks for the interview.

Photos and interview: © ferdinand dupuis-panther

Informations

Matthias Muche

http://www.matthiasmuche.com/

Matthias Schubert

http://jazzpages.com/MatthiasSchubert/

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matthias_Schubert

Other

In case you LIKE us, please click here:

Foto © Leentje Arnouts

"WAGON JAZZ"

cycle d’interviews réalisées

par Georges Tonla Briquet

our partners:

Hotel-Brasserie

Markt 2 - 8820 TORHOUT

Silvère Mansis

(10.9.1944 - 22.4.2018)

foto © Dirck Brysse

Rik Bevernage

(19.4.1954 - 6.3.2018)

foto © Stefe Jiroflée

Philippe Schoonbrood

(24.5.1957-30.5.2020)

foto © Dominique Houcmant

Claude Loxhay

(18/02/1947 – 02/11/2023)

foto © Marie Gilon

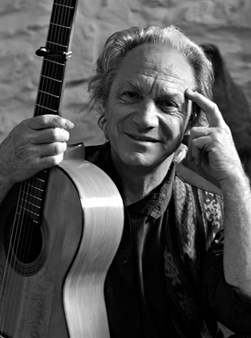

Pedro Soler

(08/06/1938 – 03/08/2024)

foto © Jacky Lepage

Special thanks to our photographers:

Petra Beckers

Ron Beenen

Annie Boedt

Klaas Boelen

Henning Bolte

Serge Braem

Cedric Craps

Luca A. d'Agostino

Christian Deblanc

Philippe De Cleen

Paul De Cloedt

Cindy De Kuyper

Koen Deleu

Ferdinand Dupuis-Panther

Anne Fishburn

Federico Garcia

Jeroen Goddemaer

Robert Hansenne

Serge Heimlich

Dominique Houcmant

Stefe Jiroflée

Herman Klaassen

Philippe Klein

Jos L. Knaepen

Tom Leentjes

Hugo Lefèvre

Jacky Lepage

Olivier Lestoquoit

Eric Malfait

Simas Martinonis

Nina Contini Melis

Anne Panther

France Paquay

Francesca Patella

Quentin Perot

Jean-Jacques Pussiau

Arnold Reyngoudt

Jean Schoubs

Willy Schuyten

Frank Tafuri

Jean-Pierre Tillaert

Tom Vanbesien

Jef Vandebroek

Geert Vandepoele

Guy Van de Poel

Cees van de Ven

Donata van de Ven

Harry van Kesteren

Geert Vanoverschelde

Roger Vantilt

Patrick Van Vlerken

Marie-Anne Ver Eecke

Karine Vergauwen

Frank Verlinden

Jan Vernieuwe

Anders Vranken

Didier Wagner

and to our writers:

Mischa Andriessen

Robin Arends

Marleen Arnouts

Werner Barth

José Bedeur

Henning Bolte

Erik Carrette

Danny De Bock

Denis Desassis

Pierre Dulieu

Ferdinand Dupuis-Panther

Federico Garcia

Paul Godderis

Stephen Godsall

Jean-Pierre Goffin

Claudy Jalet

Chris Joris

Bernard Lefèvre

Mathilde Löffler

Claude Loxhay

Ieva Pakalniškytė

Anne Panther

Etienne Payen

Quentin Perot

Jacques Prouvost

Renato Sclaunich

Yves « JB » Tassin

Herman te Loo

Eric Therer

Georges Tonla Briquet

Henri Vandenberghe

Peter Van De Vijvere

Iwein Van Malderen

Jan Van Stichel

Olivier Verhelst