Thomas Chapin

The Thomas Chapin era

© Terri Castillo

Friends and colleagues all agree: he was not finished yet. He had just begun and he had to leave too soon. Unfinished business, somebody said. He always played as if it was his last concert ever, someone else said. On Friday the 13th in February 1998, at age 40, Thomas Chapin's struggle with leukemia came to an end. His time was over.

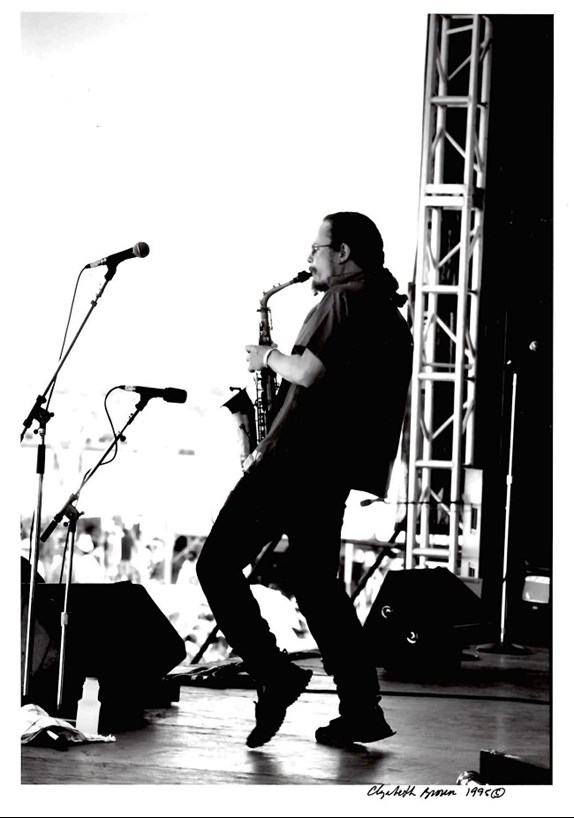

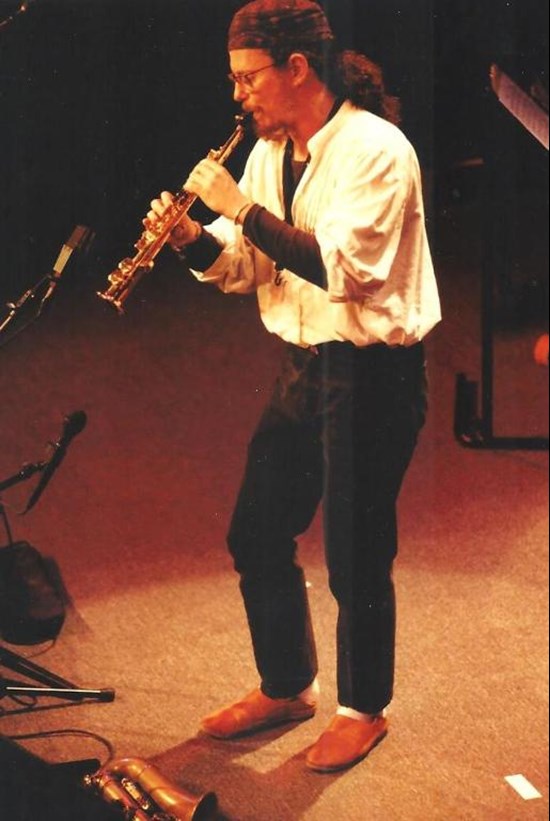

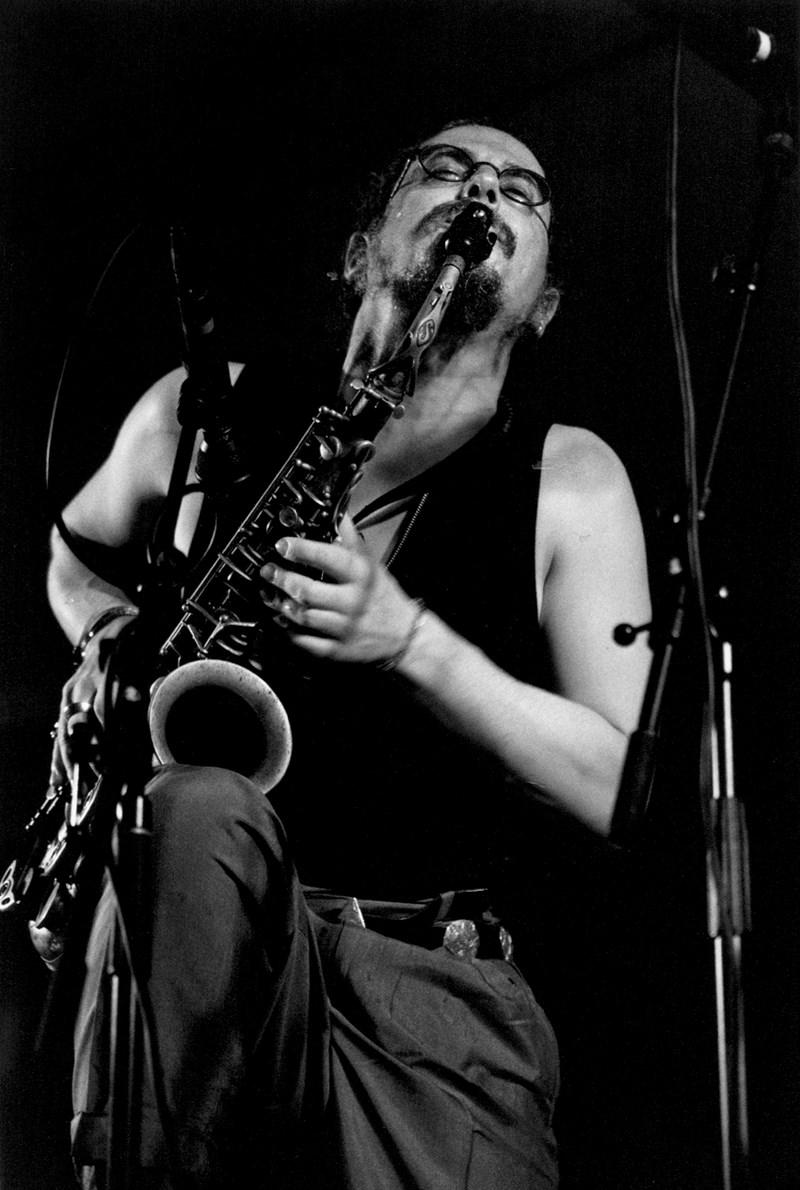

Newport Jazz Festival 1995 © Elisabeth Brown (Photo permission by Akasha, Inc.)

Newport Jazz Festival 1995 © Elisabeth Brown (Photo permission by Akasha, Inc.)

WHEN THE SAINTS GO MARCHING IN

The era of the American saxophonist, flautist, composer and arranger Thomas Chapin (° March 9, 1957) was set in the late eighties and nineties. The years in which he flourished as a musician, the years his creativity grows into a crackling fire. In his two decades of performing, Chapin is a force, a player with "monstrous chops," whose sound is individual and incomparable. He has an uncanny gift of melding all forms of jazz into a single body of music and his pathway of moving sound is so multi-directional, yet singular, so original, yet steeped in tradition, that the jazz community struggles to categorize him. As one of the few artists of his generation to exist in both the New York City's downtown experimentalist scene and in the uptown world of traditional jazz, Chapin is tireless and passionate in his pursuit of creating an edgy, engaging, cutting-edge sound that pushes jazz forward, while being fearless in showing his mainstream influences. In June 2016, Aidan Levy of the JazzTimes Magazine writes that Chapin is "considered by some to have fundamentally expanded the boundaries of the jazz discourse."

Of course his musical career started years earlier. He's born in a small town, Manchester, Connecticut, U.S.A., in 1957, and as a baby he's banging on the pots and pans (sprawled everywhere) in the kitchen much to his mother's dismay. As an adolescent he takes piano lessons as many kids do and learns the flute. In 1972 he attends a private high school in Andover, Massachusetts, and there a music teacher hears something in his playing and thrusts a saxophone in his hands. That was it! Chapin puts all his focus on the instrument and never looks back. Music will be his calling and life and 'first love.' There, too, he becomes part of an improvisational quartet, Zasis, for eight years. This energetic and free collective will have a lasting influence upon his future musical style and direction. Chapin goes on to study with Kenny Baron and Jackie McLean at The Hartt School of Music at the University of Hartford, Connecticut, 1978, and later with Paul Jeffrey and Ted Dunbar at Rutgers University in New Jersey, 1980, where he gets his BA in music. Barely graduated, Thomas Chapin joins the Lionel Hampton Big Band in 1981. Also in the Lionel Hampton Big Band then were tenor saxophonists Ricky Ford and Arnett Cobb, alto saxophonist Paul Jeffrey and trumpeter Barry Ries. Chapin stays six years as musical director and soloist on alto saxophone and flute. The band tours the world and plays on all the global festival stages. In his book “Jazz The Modern Resurgence” Stuart Nicholson remembers that in that time Hampton, to everyone's surprise, and sometimes horror, chooses ‘In The Mood’ and ‘When The Saints Go Marching In’ as an encore. No wonder that Ned Rothenberg, friend and colleague of Thomas Chapin, typifies the period Chapin works with Hampton as: “He seriously paid his dues.”

Also in 1981, he records under his own name his first-ever album, an LP, "The Bell of the Heart" with Mario Pavone's Alacra label. All tunes are original, except "Body and Soul". Pavone and Chapin had just met and were just starting out their music association. The musicians playing on "Bell of the Heart" are George Alford/Peter McEachern/Phil Buettner/Nick Makros/Lucian Williams/Mario Pavone/Emmett Spencer/Matt Emerzian.

A milestone career Trio performance at Newport Jazz Fest, 1995

After the years with Hampton, Thomas joins the band of drummer Chico Hamilton for two years and in the meantime he also plays in different contexts. A Latin classical chamber ensemble, several flamenco groups, a freefunk-free-jazz-rock band Machine Gun, the straight ahead Connecticut-based jazz band Motation, the NY-based Peruvian jazz singer Corina Bartra, and his Brazilian-Afro Cuban ensemble Spirits Rebellious and album by the same name, (Alacra, 1989), greatly influenced by his hero, Brazilian composer-musician Hermeto Pascoal.

In April 1984 he records a second album under his own name of mostly original tunes, except Fats Waller's Jitterbug Waltz, and is well received when it is finally released in 1990. The CD is "Radius” (on guitarist-friend Bob Musso's MUWorks Records label; Musso is also the album's engineer), with pianist Ronnie Mathews, bassist Ray Drummond, drummer John Betsch, Ara Dinkjian, oud and Sam Turner, congas. Still today a highly-acclaimed work, this engaging record shows how much Chapin was affected by legends like Jackie McLean, Eric Dolphy and Roland Kirk.

Quartet CD release in 1990 (MU Records)

LIVE AT THE KNITTING FACTORY

On the eve of the nineties Thomas starts his trio that develops into his working band par excellence. The trio becomes his laboratory where he examines and tests his possibilities, where he experiments with new formulas, where his own boundaries are challenged. Summer 1989 the Thomas Chapin Trio debuts at The Gas Station in New York's East Village. Bassist is Mario Pavone, who has already formed a close bond with Chapin because of various previous projects they have worked on together, on drums is Pheeroan AkLaff. The trio performs at this small festival organized by Bruce Lee Gallanter, founder of Downtown Music Gallery, a prominent new-music record store in New York City. A half year year later, in December 1989, Gallanter gives them the opportunity for their first concert at Michael Dorf's iconic downtown club, the Knitting Factory, that just exists two years, and became, just as CBGB’s and The Kitchen, the new temple for the New York avant-garde and alternative music. A recording from that concert can be heard on the compilation “Live At The Knitting Factory Volume 3”, and is the start of a close relationship between Thomas Chapin and the Knitting Factory Records label which lasts until Chapin's death in 1998. Chapin’s the first artist with an album of his own on the label that was founded in the beginning of the nineties. He’s also the one with the most albums under his own name for the label.

'Spirits Rebellious' release of original Brazilian music, 1989 (Alacra)

In the meantime it’s now Steve Johns on drums. He stays two years with the trio and plays on two albums with Chapin and Pavone: “Third Force” in 1991 and “Anima” in 1992. The trio’s proper sound, their own language based on compositions and arrangements by Thomas Chapin, slowly matures and seems to come in full bloom, with the arrival of drummer Michael Sarin. He already appears as second drummer on “Anima”, but in 1992 he replaces Johns and gives birth to the definitive version of the Thomas Chapin Trio. For the next six years, this triumvirate plays as a jazz beast with three heads: Chapin, Pavone and Sarin are in perfect match, improvisation and composition are one whole, jazz tradition and free experiments fit nicely together. They sound, in critic Kevin Whitehead’s words, as “hotly, vamping post-free jazz”.

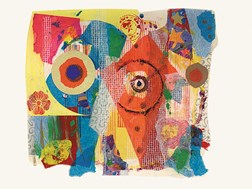

Collage by Thomas Chapin, 1991 (Art by permission of Akasha, Inc.)

In December 1992 the Chapin trio records a CD with six horns. It is the first time Thomas experiments with a larger ensemble of brass players and this gives the trio compositions a new dimension. It results in “Insomnia”, considered a brilliant and outstanding album with Al Bryant, trumpet, Frank London, trumpet, Curtis Folkes, trombone, Peter McEachern, trombone, Marcus Rojas, tuba and Ray Stewart, tuba. The music goes from typical New York avant-garde from the nineties to more mainstream jazz in which he can use the experiences from his Hampton period. And in addition he shows his ability as an arranger and composer from open themes with a lot of improvisation space. Four years later he extends the trio with a string section on the CD “Haywire” which receives similar accolades and praise for another expanded trio assemblage with Mark Feldman, violin, Boris Rayskin, cello and Kiyoto Fujiwara, bass. It includes a beautiful , haunting rendition of 'Diva,' a composition by Italian jazz trumpeter Enrico Rava.

SJU Jazz Festival, April 9th, 1994 © Marinus Lavèn

YOU DON’T KNOW ME

1992-1996 is probably his most productive period and also his most creative. In these four years he releases another trio CD “Menagerie Dreams” (1994), with saxophonist John Zorn and poet Vernon Frazer as special guests. Yet to come are his last Trio albums on the Knitting Factory Records label which include what Chapin considers his best-ever work, "Sky Piece" (1996).

Also in these formidable years, the trio gives milestone world-stage career performances: in 1993 at the Madarao Jazz Festival, Japan, which showcases his trio in one of the first overseas big-stage appearances, and also on that date, Thomas plays with legend Betty Carter. While crossing the Pacific Ocean to return to the U.S., the trio stops in Hawaii and gives a stellar performance at the prestigious Honolulu Academy of Arts.

Thomas and Betty Carter at Newport Jazz Fest in Madarao (Japan).

Photo permission by Akasha, Inc.

Says Mario Pavone, "He was terrified of what key she might sing 'Speak Low' in ( singers always sing in unusual keys ). But this [photo] is after .. and he had nailed it !!!!"

In 1995 the trio gives what is considered by many to be a breakthrough and unforgettable U.S. performance at the renowned Newport Jazz Festival in Rhode Island. You can still feel the impact the artist made on the lives of all that came in contact with him. Laurence Donohue-Greene, Managing Editor of The New York City Jazz Record, recalls, “Thomas performing at Newport in 1995… That was a life highlight in music for me. Over 20 years ago and I vividly remember that set to this very day as still being one of the greatest Newport Jazz Festival sets I’ve ever seen.”

In 1996 at the prestigious Umbria (Summer) Jazz Festival, in Perugia, Italy, the trio plays to standing ovations in an unprecedented 10-night marathon at Club Il Pozzo. Ironically, because his illness is on the near horizon, an 'epiphany' Thomas has during this significant summer engagement in Umbria won't be tested: " ... The standing ovations made Chapin realize that his 'forward looking' music had reached the point where it was appealing to a more extensive and varied audience than he had imagined," New York Times critic Mike Zwerin writes. To add to the pile-up of heartbreaking losses to come as the forthcoming adversity starts to overtake the impressive successes for Chapin, an invitation to return to this important Fest must be forsaken. Carlo Pagnotta, director of Umbria Jazz Fest, asks Chapin to bring back three of his groups for the Winter, 1997 Fest: his trio, a quartet or quintet, and the trio plus strings or brass ensemble. Chapin's tragic diagnosis of illness at the end of January, 1997 sadly prevents him from fulfilling this meritorious return engagement.

(Editor's notice: For Zwerin's entire article, scroll down to after 'The Press' quotes, to read "Thomas Chapin's Last Europe Interview.")

SJU Jazz Festival, April 9th, 1994 © Marinus Lavèn

Also in these years are some memorable NYC downtown concerts, Chapin appears as guest with a hiphop-freejazz project (Species Compability by Ken Valitsky), and also plays improvisational music with Under Cover Collection Band with a.o. Tom Cora. He does some formidable performances with legendary avant drummer William Hooker in 1992, and it results in the posthumous CD release "Crossing Points" on the Lithuanian NoBusness label (2011). Besides these avant-garde projects the versatile saxophonist maintains his strong mainstream side: Chapin as hardbopper with a sound referring strongly to Phil Woods.

For Arabesque Records, a jazz and classical label, he makes two albums: “I’ve Got Your Number” (1993) and “You Don’t Know Me” (1994). Here Chapin leaves the trusted trio nest and works in a quartet and quintet setting with people as Tom Harrell, Peter Madsen, Reggie Nicholson, and old friends as Ray Drummond, Ronnie Mathews and Steve Johns. These two albums, much praised, absolutely place Chapin as a jazz master who firmly belongs equally in the traditionalist camp as the avant garde. As critic Chris May in allaboutjazz wrote, "[He] was his own man, but his music resonated loudly with the work of reed giants from an earlier age."

The following year, 1995, he starts a session for Knitting Factory with Anthony Braxton on piano. Together with Dave Douglas, Mario Pavone and Pheeroan AkLaff they play “Seven Standards”: wonderful solo moments but not enough interaction. Much more interesting is “The Fuchsia” (1997 release on Koch) from a couple of months later: the only recording of the Peggy Stern/Thomas Chapin Quartet, one of his lesser known mainstream projects with Drew Gress on bass and Bobby Previte on drums. There’s a great understanding between Chapin and the pianist and composer: Stern delivers most of the compositions and Chapin feels very comfortable with them. It’s an album with plenty of pleasant surprises, funky rhythms, nice melodies and strong interplay. In addition it’s one of his few recordings with a pianist; nevertheless totally different than the improvisation duo with the late celebrated NY free pianist Borah Bergmann (“Inversions”, 1992) or “Watch Out” in quartet with pianist Misako Kano, Kyoto Fujiwara and Matt Wilson, recorded in 1996, but posthumously released in June 1998. Also in 1996 with Netherlands musicians, Vandoorn (Ineke van Doorn, Marc van Vugt) + Thomas Chapin: President for Life (VIA, PIAS; Belgium) CD was released..

Thomas Chapin Trio @ North Sea Jazz Festival, The Hague, Netherlands, 1995

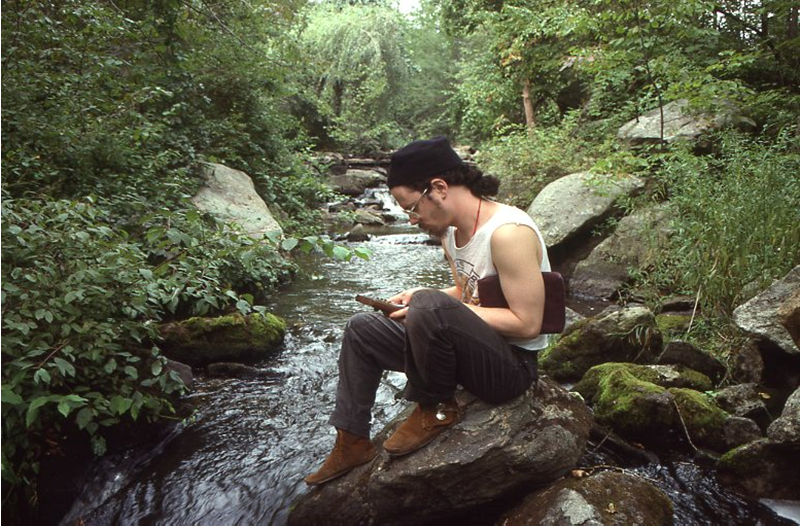

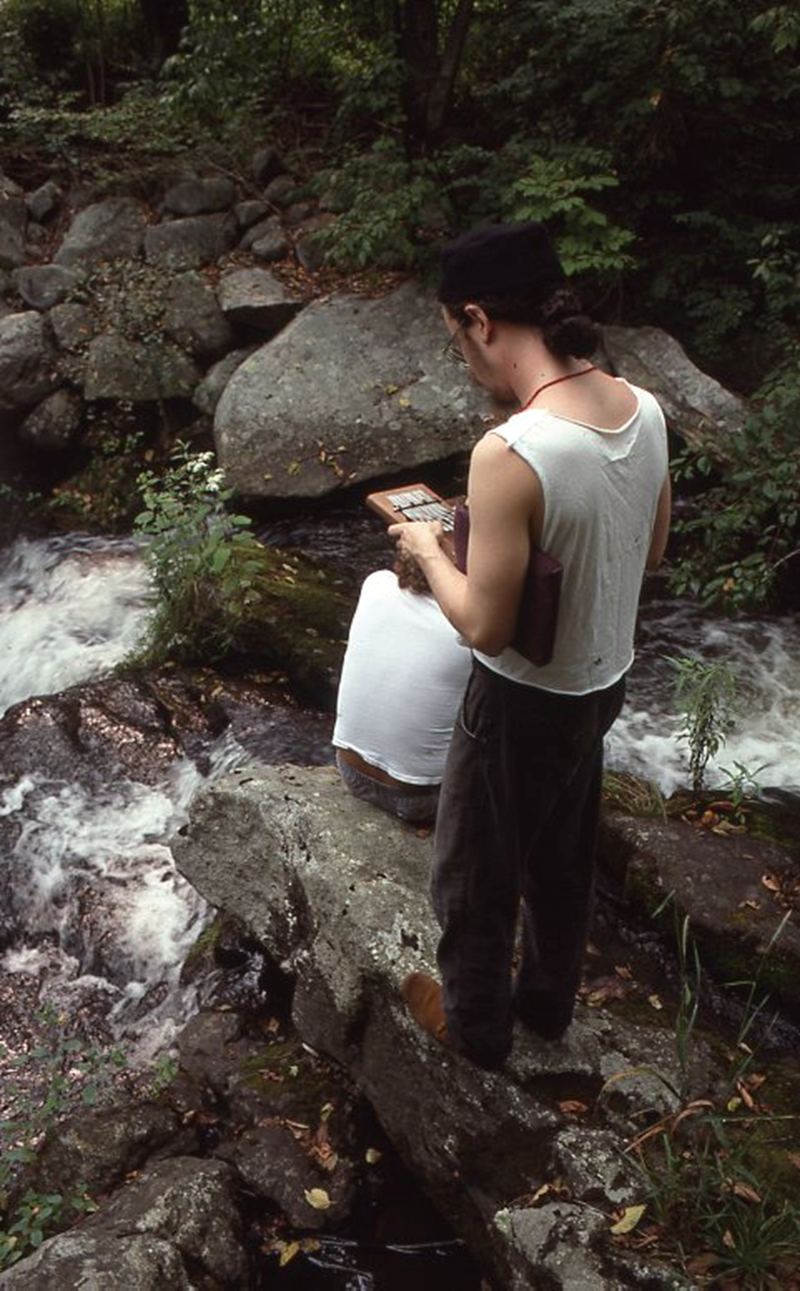

After eight years of great and still-rising success with the trio, Chapin takes a well-deserved break in early 1997 to travel to, for him, the beloved continent, Africa, a place of lifelong musical resonance and influence. Over the years, he's been several times to visit and explore and on one occasion, he plays in a Cape Town club at the invitation of Connecticut bassist-friend Hotep Galeta, who was living in South Africa at the time. But on this new trip in early 1997, he visits eastern and coastal area, Uganda, Tanzania and Zanzibar. In Zanzibar he meets local musicians and helps a French musicologist record them. It is here, sadly, that Chapin's unbelievable downturn begins. He gets sick with fever, is weakened and must return to New York. Once home, he is immediately diagnosed with leukemia. It is February, 1997. The treatments last for a full year. There are some hopeful moments, but tragically he is not to recover. Mario Pavone, critics and others lament this fate, describing the up-to-that-point, undeniable upward movement of Thomas and the music: "The plane was just gaining altitude."

In the Fall of 1997, Chapin is too weakened by his leukemia to continue his work. He stops performing and there are no more recordings after a very busy previous year of sessions with musician-friends: Ineke Vandoorn, Misako Kano, Mario Pavone, Michael Blake, Barbara Dennerlein and Pablo Aslan. Together with Aslan, a bassist, originally from Argentina, and pianist Ethan Iverson they had formed Avantango as a septet in 1994. They play “spontaneous tango” as it is called by Aslan in the liner notes from the now-Trio group (with Aslan, Chapin and Iverson) CD “Y en el 2000 también” (1996): tango trying to incorporate jazz and free improvisation. Thomas' original tune, "Telling Comment" is included in the recording.

Throughout his musical years, Chapin has been using a cross pollination between jazz and non-Western music, world and indigenous music in his compositions: Armenian-American oud master-friend Ara Dinkjian plays on Radius (1984) for instance, or the suite “Safari Notebook” (from “You Don’t Know Me”, 1994) in which Chapin incorporates impressions from his journeys through Africa and Namibia. And on I've Got Your Number, 1993, he uses the master Afro-Caribbean percussionist Louis Bauzo on congas. Chapin studied with Bauzo in 1991 through a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, Amercan's prestigious public funding body. "For all the diversity of his musical experiences," writes bassist Vernon Frazer in the liner notes, "Chapin is no musical dilettante flitting from one genre to another, his commitment to music in all its varieties is total. 'I do it for the joy of playing, of becoming the music that I'm playing.' says Chapin. 'It's not like putting on clothes. It comes from within. I'm exploring different facets of my personality.'" Frazer continues, "Chapin's voice remains constant, spicing each musical dish with his distinctive, energetic sound."

With AVANTANGO

AEOLUS

The last session with the Thomas Chapin Trio was recorded in July 1996 in the studio by his trusted engineer Robert Musso. It was released on the Knitting Factory label as “Sky Piece”, considered by many still today as one of Chapin's outstanding works of his career. His mainstream and avant-garde jazz are forming into a harmonious whole. Free trio improvisations alternate with nicely built and engaging compositions with subtle hints of his interest in African music; the only track he hasn’t composed himself is Monk’s “Ask Me Now”. Carefully dosed exotic sounds give color to the music: Thomas not only plays alto sax and sopranino, but also flute, bass flute and wooden flute and he uses bells, toy flutes and an alarm clock. Called during these trio years, 'the flute master of his generation,' Chapin's dexterous and consummate flute playing in Sky Piece testify to his undeniable command and dominion over the instrument. The common thread through the album seems time, the merciless clicking of the clock, the realization that his time has come. It’s only just before his death that he could make the recording ready for release.

But there was more unreleased trio music on the shelf: "Night Bird Song" was recorded at Kampo Cultural Center, NYC, from August and September 1992, for instance. But we had to wait until 1999 to hear this music on the Knitting Factory label. It was Thomas’s wish that this CD be released after “Sky Piece” (1996). Both CD’s have three compositions in common. The arrangements are not very different, but nevertheless there is a clear difference. On “Sky Piece” there’s balanced beauty--the trio is at its peak; while “Night Bird Song” is intense and full of wild enthusiasm. The pieces sound rougher and less polished: this is the young trio in a promising growth phase. One of the pieces that was never released before is “Aeolus”, a touching duet with Mario Pavone: brilliant interplay from two musicians that understood each other like no one else. No wonder Pavone records the same title with his own Nu Trio for “Remembering Thomas” (Knitting Factory, 1999), his homage to his great friend and colleague.

“Aeolus”, Thomas’s ode to the god of the wind, is also the last music he blows through his instrument. His last public performance is in Manchester, Connecticut – his birthplace - on February 1st, 1998. Two days later he’s back in the hospital and on February 13th Thomas, at age 40, lost the fight against his leukemia. And that’s the end of Thomas’s era.

SJU Jazz Festival, April 9th, 1994 © Marinus Lavèn

Based on the original text (in Flemish) by Jeroen Revalk (published in the paper version of Jazz'halo 1999, #4) and updated (in English) by Teresita Castillo Chapin (July/August 2016).

Translation to English: Jos Demol (with special thanks to Teresita Castillo Chapin for the corrections) (June 2016)

Visit http://www.thomaschapin.com/ and http://www.thomaschapinfilm.com

Electrifying Night For Thomas Chapin

February 03, 1998 | By OWEN McNALLY; Courant (Connecticut) Jazz Critic

Not even the word "electrifying'' has quite enough emotional voltage to describe the jolting impact of jazz musician Thomas Chapin's surprise performance Sunday night at a benefit held to defray the skyrocketing medical costs of his battle with leukemia. Halfway through the standing- room-only concert at Manchester's Cheney Hall, the buzz was that Chapin might be not be well enough to appear at the fund-raiser, which featured dozens of musicians donating their efforts.

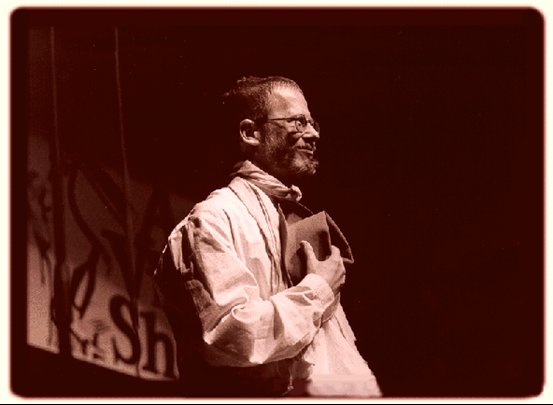

But midway through the second half, bassist Mario Pavone, a longtime friend and collaborator, announced that Chapin was not only in the house but would perform an original piece on flute. Chapin, who was sitting in the wings with his wife, Terri, walked out on stage, looking gaunt and ill but spiritually resilient, smiling widely while enveloped in warm, loving applause. Warning that he might become overwhelmed with emotion, the 40-year-old Manchester native expressed thanks for the benefit, which turned into a giant Chapin love fest.

"I've been blessed to know so many of you. . . . So much adds to the healing,'' Chapin told the packed house of 350 friends, fans and family members.

Deeply moved, he played an emotion-drenched flute solo. For a few bright, magical moments, it seemed as though the clock had been turned back before his harrowing ordeal began with the debilitating disease and series of chemotherapy sessions, transfusions and hospitalizations. At the height of the instrumentalist/composer's growing national prominence one year ago, he was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia, a disease in which malignant cancer cells are found in the blood and bone marrow.

Chapin's impassioned, soaring solo filled the elegant, old Victorian- era theater with a powerful, real-life drama. Spellbound, the audience sat in awed silence until the final note.

Bowing to a standing ovation, Chapin walked off stage and was quickly swallowed up in darkness. Then he popped back out into the limelight, bowed again and placed his right hand over his heart.

Photo permission by Akasha, Inc.

When the final bar was sounded, Chapin's mother and father, Marjorie and Edward, stood at the apron of the stage, watching their son surrounded by well-wishers.

"His determination to live will pull him through, I hope,'' Chapin's father said.

"I was playing right along with him in my mind because, I wondered if he would have the strength to do it,'' Chapin's mother said of her son's first public performance since last summer. ``It's out of our hands. So we hope for the best.'' ###

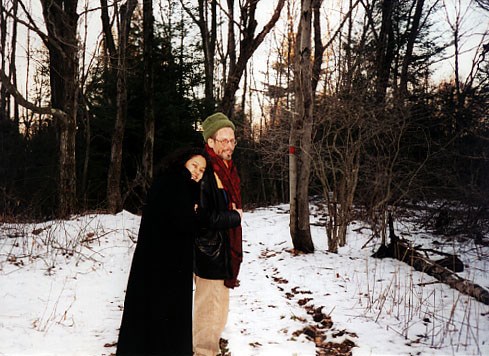

Thomas and Terri, circa 1988 (Photo permission by Akasha, Inc.) © Connie Walker

JOURNEY OF AN ILLNESS

Note by Terri Castillo Chapin: "I'd like to share this timeline for the year of Thomas's illness."

• Late-Jan. 1997 Thomas goes to Africa: Uganda, Tanzania and Zanzibar. It's a personal visit, his fourth trip to the continent where he also meets local musicians. The weather is very hot, and he is treated several times for severe sunburns.

• Mid-Feb. In Zanzibar, Thomas gets sick with fever. Tests are taken, but inconclusive, and he returns home to New York City.

• Mid-Feb.-March Thomas is diagnosed with leukemia and in the hospital undergoes a first round of chemotherapy. He returns home on Easter Friday, fatigued, but tranquil. We are happy and grateful for this time and privacy.

• April -June Thomas has a second round of chemo, then is declared to be in remission. He's told by doctors to play his music, live his life.

• July - Sept. Thomas makes public performance gigs in Canada, New York City and Connecticut.

• Early Oct. Thomas relapses and the leukemia is back. A sad time for everyone and Thomas especially. This time he chooses to undergo a still-new experimental stem cell transplant procedure and returns to the hospital.

• Oct. 15 In a truly beautiful moment, Thomas and Terri are moved to marry in the hospital after a ten-year relationship.

• Late Oct. The leukemia rages and the hoped-for treatment is abandoned. Thomas declines further rigorous chemo. His doctor says, "You've chosen wisely." There are no more medical options. "We're living in the realm of the miraculous," Thomas says to an interviewer.

• Nov. - Jan. 1998 Thomas (and Terri) turns to alternative therapies, experimental drugs and spiritual regiments, including seeing the Dalai Lama's physician, Ven. Dr. Yeshi Dhonden, a Tibetan monk, in New York City. It's all a terrifying walk into darkness, grasping at straws at every turn with no real success. Throughout this time, Thomas, not knowing his end, says, "I love my life. I've had a great life," and pleads many times to me and to his brother Ted, "Don't let my music be forgotten. Keep it going. Keep it out there."

• Feb. 1 Now very much weakened, but lucid, Thomas makes an appearance at a benefit concert for him in his hometown of Manchester, Connecticut. He surprises all and fulfills his long-time wish: 'to play one more time.' On the stage with his flute and reunited with his Trio, Mario Pavone and Mike Sarin, he plays his ballad-composition 'Aeolus' with soaring power and with faltering, too. At the end, with hat to his chest, he bows to the standing audience who are moved to tears. It is to be his last performance.

• Feb. 2 The next day at his parent's home in Manchester, Connecticut, Thomas wakes up with a fever.

• Feb. 3 A day later, Thomas is taken to Rhode Island Hospital. The doctors' shake their heads: the x-rays are dire and show his lungs are filled with liquid. I say to Thomas, in effect, "This time"--there had been many times we had to go to the hospital to check his condition-- "may be a very hard time. I may not be able to get you out of here." That was the way I put it. Thomas looks beatific, serene, and says calmly, "I'm at peace because of Sunday." Meaning when he played "one last time," the evening of the benefit concert. He had been saying many times, "I want to play one last time. I want to play one last time." I'm in awe. What more beautiful place could he be in if he were to leave us now? I feel great solace and comfort. In his hospital room, we say what will be our last "I love you's." I leave the room. The doctors and nurses gather around and attend to him. Thomas slips into a coma-induced sleep.

• Feb. 4-12 The doctors work vigorously each day with different regimens, including experimental, to reverse his condition, but his vitals remain unchanged and he declines rapidly.

• Feb. 13 Ten days later, Thomas passes. His family is gathered around his hospital bed and 'Sky Piece' plays from the recorder.

Thomas and Terri, Feb. 1998, toward the end of his year of illness,

just before he performs 'one last time' at the benefit concert in Connecticut

(Photo permission by Akasha, Inc.)

Terri concludes: "It was a long, hard year; Thomas had endured some of the most punishing days a human being could suffer. But his 'warrior spirit,' his courage and determination to live, his hope and his faith --and his humor, too *-- inspired all of us. He was a great musician, yes, but also a profound and compassionate human being and a huge soul. He tried to live his life 'awake' and in awareness that each moment mattered. He practiced resolutely: Be Here Now. And when he made a mistake or fell short, he humbly said, 'I'm sorry. I'll try to be better.' He did and he was. His last words to his fans at each of his benefit concerts were: "Give blood. Give blood in everything you do." This is how he lived not only each day, but to the very end. We all still miss him so very much."

* A big trait of Thomas was his humor, his infectious laughter (he loved to laugh--he loved puns! He loved cartoons!) and his trademark, inimitable, deep "diabolical" laugh (wicked! unmistakable!), his joking nature on and off stage, his "trickster" and "fool" nature, his irony and wit (very quick! and wry, too--and if you could take it and dish it right back, he LOVED that!) was very unique and a special quality of his.

SJU Jazz Festival, April 9th, 1994 © Marinus Lavèn

Quotes over the years by Thomas Chapin:

“Playing, for me, is about changing my state of mind, moving out of my ordinary self. I’ve noticed that when I play, it’s almost like a different person takes over, someone who I don’t deal with in my day to day life, but who is inside me. I try to let this creative force take over. I try not to get too much into my conscious thought. It’s more a matter of setting up conditions—gaining mastery of my instrument, mapping out structures, that kind of thing—that will allow the conduit to open. And when the conduits do open, when that other person takes over, I just sit back and watch the show, and see what comes out. To me, that’s what’s divine about all of this. That’s why I love to play.”

“Compositions are a balance. It’s like saying, ‘for every poison there’s an antidote‘—if a composition gets too sweet, you have to mess it up, on purpose.”

“All my ideas are influenced by my work in Lionel Hampton’s big band, but it doesn’t encompass the whole range of what I do now.”

“The situation [with the Trio] is very freely harmonic. It’s the place where I give my imagination free rein.”

“You need opposition, friction. Without friction there is no heat, no energy, no life. You strive towards higher things, but you also have a body that wants to swing, that has erotic desires, that has to eat. Those are the devils, good and bad, that you should remain on good terms with. Sounds that are nothing but sweet end up not being sweet at all; it’s when they’re bittersweet that they become beautiful… “

“There are a lot of different ways to structure your life and your music. Some people need to define what they are. I don’t. For me, it’s not a matter of negating things. It’s about accepting all that’s out there and selecting….One day last week I worked with Mario Bauza’s Afro Cuban Orchestra, recorded a demo tape of flamenco with a chamber ensemble for a Spanish dance company, and played Argentine jazz with Avantango at the Nuyorican Poets Café.”

“Once in a while I like to listen to polkas—that’s no sin.”

“If I look at my life, it’s improvised in a way. All my art is improvised so I try to find a less deliberate way of doing things. I do a certain amount of work. When I play, I want to play. I don’t want to play anything contrived.”

“If I’m really going to be a ‘free’ musician, I should be free to do whatever I want to do. I should be able to step in and out with equal facility. If I want to play it all inside and it feels good, then why not?”

SJU Jazz Festival, April 9th, 1994 © Marinus Lavèn

Thomas Chapin, 40, Raucous Jazz Musician

By PETER WATROUS FEB. 15, 1998

Thomas Chapin, one of the more exuberant saxophonists and bandleaders in jazz, died of complications due to leukemia on Friday at Rhode Island Hospital in Providence, said a friend, Sam Kaufman. He was 40.

Mr. Chapin was one of jazz's more extraordinary musicians. A typical solo of his moved easily between traditional jazz and the sonic explorations of the avant-garde, and in concert he was a showman, using yells and roars and howls to charge his performances.

Mr. Chapin was a fan of two of the more raucous saxophonists in jazz history, Rahsaan Roland Kirk and Earl Bostic, and he approached his shows in part as theater. None of his extroversion diminished the sense that Mr. Chapin was deeply studied, and in his playing one heard everything from folk music of the world to be-bop, from classical music to early jazz. And Mr. Chapin was one of the few musicians to exist in both the worlds of the downtown, experimentalist scene and mainstream jazz.

He came to his breadth of knowledge naturally. Mr. Chapin began his serious studies in the early 1980's, attending the University of Hartford and studying with the saxophonist Jackie McLean. He later graduated from Rutgers University, after studying with the pianist Kenny Barron. The schooling he received allowed him to take over the leadership of Lionel Hampton's orchestra for six years, starting in 1981, and also maintain a position in Chico Hamilton's band as a saxophonist.

But Mr. Chapin had other ideas, and in the late 1980's he formed his own groups, most notably a trio with the bassist Mario Pavone and the drummer Steve Johns. And he entered the fertile world of the Knitting Factory; Mr. Chapin was the first artist signed by the club's record label, Knitting Factory Records.

For nearly 10 years Mr. Chapin pursued his own music, working with the trio at festivals and clubs around the world, and also arranging larger groups. And he spent a good portion of his time working with the more important names in various factions of jazz. He performed with John Zorn, Dave Douglas, Ned Rothenberg, Marty Ehrlich, Ray Drummond, Ronnie Mathews, Peggy Stern, Tom Harrell, Anthony Braxton and many more.

Over his career Mr. Chapin recorded about 15 albums; his most recent, ''Sky Piece'' (Knitting Factory), a trio recording, was recently released.

He is survived by a wife, Terri Castillo-Chapin of Queens.

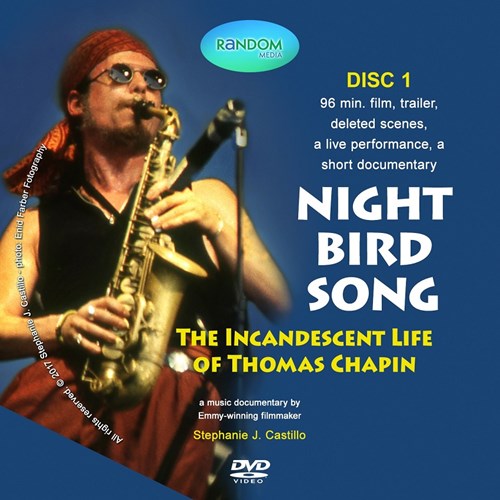

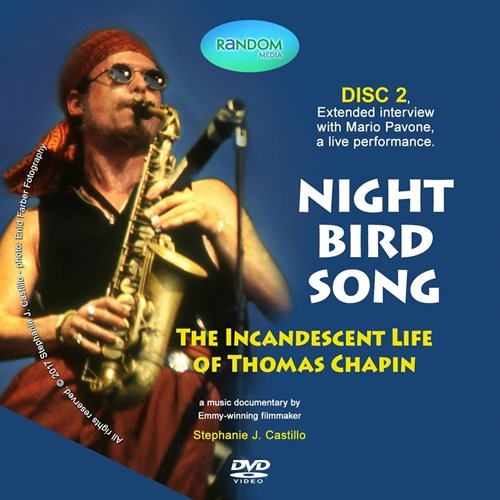

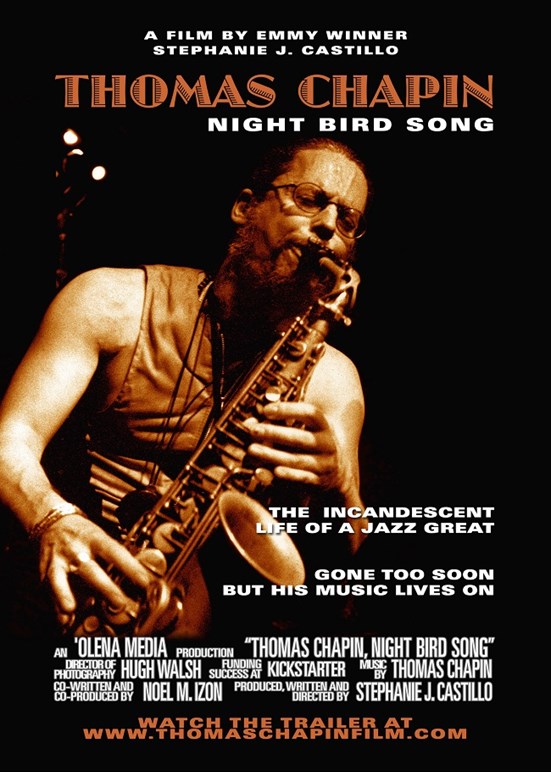

FILM ABOUT THOMAS CHAPIN & ADDED RARE FULL PERFORMANCES

Here's the content breakdown for the 2-disc CD, 6 hours, total:

Disc 1:

- The 96 min. version of the film

- The 2 min. film's trailer

- The deleted scenes (25 mins.) featuring

- US & Europe tour;

- The Netherlands tour;

- The Thomas Chapin Quartet;

- What is Jazz Debate;

- Thomas & Bebop;

- Thomas's Legacy.

- Live Trio Recording Session with Michael Sarin on drums (1 hr.)

- Terri Castillo Chapin's short documentary about Thomas, DANCING CHICKEN MAN (10 mins.)

Disc 2:

- Uncut interview for the film with Mario Pavone, bassist for the Thomas Chapin Trio (150 mins.). Trio, Thomas, jazz, Mario history galore! A feast of great stories and information.

- Live performance at the Knitting Factory with Thomas Chapin Trio with Steve Johns on drums. (1 hr.)

WHERE TO BUY?

- For the Special Edition, 2 Disc, DVD, go to Moviezyng.com -- $20.99

- For Downloads or Rentals (but no special/extra features this is just the film), go to ITUNES to View ($4.99) or Buy ($14.99)

- Or buy the DVD in U.S. at: Barnes and Noble ($21.99) & Best Buy ($19.99)

The special additional features, including rare live performances of the Trio, informative lengthy interview with Mario Pavone, etc., are not included in digital downloads when viewing the film at iTunes, Amazon Prime or other digital download platforms. Best to buy the Special Edition DVD hard copy with extra content at Moviezyng.com or see more at nightbirdsongfilm.com to buy, download/stream and other facts and commentary.

Customer Reviews 5 STARS

A powerful doc on a master musician

by TheKuttleFish

"Having been a fan of Thomas Chapins since his death, I was very much looking forward to the opportunity to watch this film, and it in no way disappointed. Watching his final performance moved me to tears. Highly recommended, especially for those who don't know his work, you're in for a wonderful, perhaps life changing, surprise."

___________________________________________________________________________________

Film credits:

Stephanie J. Castillo (3/21/1948 - 3/8/2023), filmmaker, Thomas Chapin, Night Bird Song: castillosj@aol.com

Watch the film's trailer: www.thomaschapinfilm.com

You'll find a very complete discography by Emanuel Maris here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Chapin

THOMAS CHAPIN TRIO: Mario Pavone, Mike Sarin and Thomas Chapin

(Photo permission by Akasha, Inc.)

NOTE: Besides the Alive 8-CD box set which contains all of the Thomas Chapin Trio music that was released by Knitting Factory Records, 1998, --This music is now owned by Thomas Chapin's non-profit, Akasha, Inc.-- there are two other posthumous releases:

1. Ride (Playscape Recordings), 2006, is the first live European Trio concert ever released of a performance at the North Sea Jazz Festival, 1995, The Hague, Holland, with Thomas Chapin, alto sax and flute, Mario Pavone, bass and Mike Sarin, drums.

2. Never Let Me Go, (Playscape Recordings), 2012, is a 3-CD set of Thomas Chapin last quartet performances in NYC in 1995 and 1996. Disc 1 and 2 are from Flushing Town Hall, Queens, NYC, Nov., 1995, with Thomas Chapin alto sax and flute, Peter Madsen, piano, Kiyoto Fujiwara, bass, and Reggie Nicholson, drums. Disc 3 is from the Knitting Factory, NYC, Dec., 1996, with Thomas Chapin, alto sax and flute, Peter Madsen, piano, Scott Colley, bass, and Matt Wilson, drums.

1996 © Enid Farber (Photo permission by Akasha, Inc.)

Quotes from Colleagues and Friends:

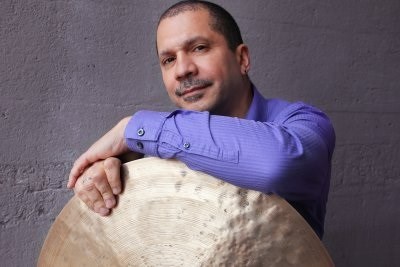

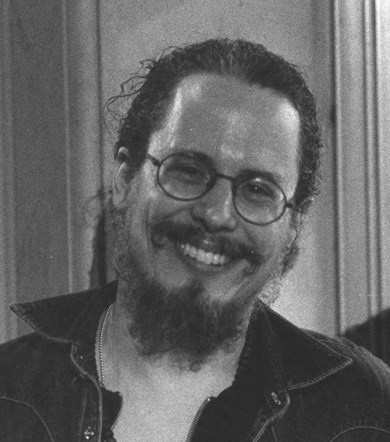

Mario Pavone © Steven Laschever

I first met Thomas in the summer of 1980 at a Big Band Mingus Tribute Concert at Buhnell Park in Hartford, Connecticut. The band was stocked with A list New York players (Junior Cook, Bill Hardman, Ray Copeland and others, as well as the most prominent musicians from Hartford (Paul Brown, Peter McEachern, Mike Duquette, Joseph Celli and others). Each time Thomas stood up and soloed , the huge crowd went crazy .. Roaring with wild applause !! I was blown away ! We met after the performance and thus began our 18 year adventure filled journey together. During all those years he never played with any less brilliance, virtuosity, energy and emotion than he did that summer day.

His fiery genius, deep commitment and strong taskmaster qualities led the defining Trio ... with Mike Sarin and myself, to worldwide critically acclaimed performances until his tragically early passing.

Mario Pavone

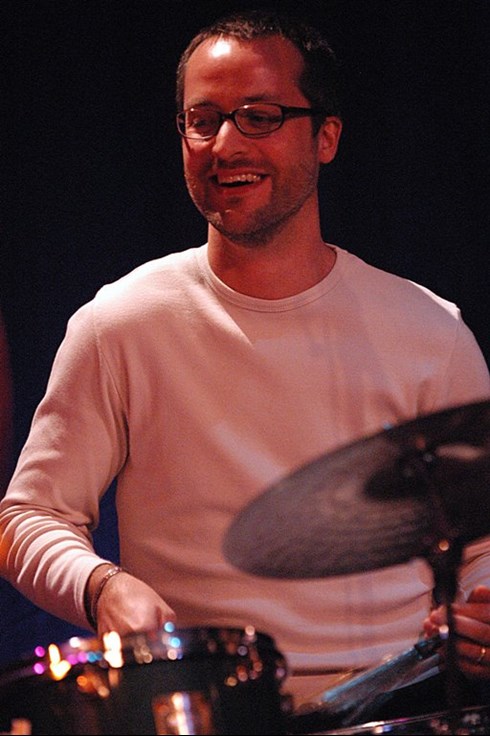

Michael Sarin © Jacky Lepage

The time I spent with Thomas and the Trio playing, traveling, and sharing a friendship was truly a joy and a blessing. He embodied most of what I sought out in New York City's jazz and improvised music community: an openness, curiosity, and willingness to embrace any-and-all musical styles and influences in forging a unique and personal voice and artistic vision.

I found Thomas to be comprised of many facets, some at odds with one another from time to time. His constant dedication to availing himself of the creative spirit, and the ensuing artistic output thereof, were a way he made sense of these various aspects. And the results were thrilling and powerful for all who saw or heard him perform; or viewed his collages; or chatted with him about any of his myriad interests.

He was a traditionalist; highly creative; rigorous; restless; intelligent; generous of spirit; curious; proactive; loyal; vulnerable; disciplined; AND he loved to laugh!!!!

Of course, we all miss his music--well, the music he would be making if still alive today. But those who knew him miss Thomas, the person--his friendship and laughter. He was a true artist and unique spirit!

Michael Sarin

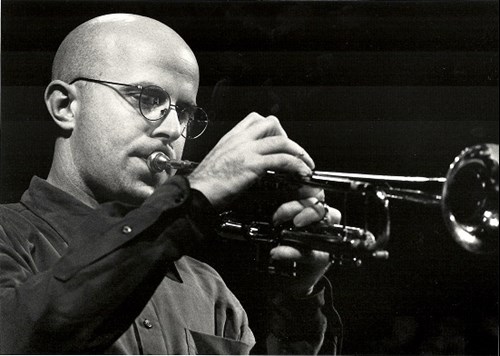

Dave Ballou © Jacky Lepage

Dave Ballou © Jacky Lepage

Thomas Chapin, to me, was an example of what jazz musicians of his generation have become: musicians of broad influence, depth and scope. I do not recall if I ever met Thomas. In 1994, I moved to Brooklyn to engage the creative music scene developing at that time. Thomas was one of the people that participated in the music developments that have become identified as downtown (Knitting Factory et al..) but he was not afraid to show his mainstream influences. Through my associations with Thomas’s bandmates and by arranging his music for several tributes surrounding the release of the film, I am stunned by his energy, enamored with his recordings and grateful for his drive and commitment to the art of improvised music. We can all learn from Thomas to trust our impulses and to have the courage to live creatively.

Dave Ballou

Michael Musillami © Simon Attila

So much can, has, and will be said about Thomas Chapin. Many layers, and like all of us, many Thomas's under one skin. So, I'll pick two pieces of how I frame him in my mind.

First, EMOTION: He seemed to channel his emotion, undistracted by outside influences, but still consider what was around him before, during, and with foresight, after. For me, this is the essence of it all. The music learning is just a vehicle for emotion. Some write, some run, some tell jokes, TC did it through music, his way. We all do it, just in a different way.

Second, SOUND: His sound was singular. His. The music voice. Was he the greatest saxophonist ever? Yes? No? It doesn't matter. He was TC. He had his voice and a story to tell while he was here. I believe he knew his time was limited. We know these things. Our body tells us in subtle ways.

He was my friend, teacher, and one of the cats.

Michael Musillami

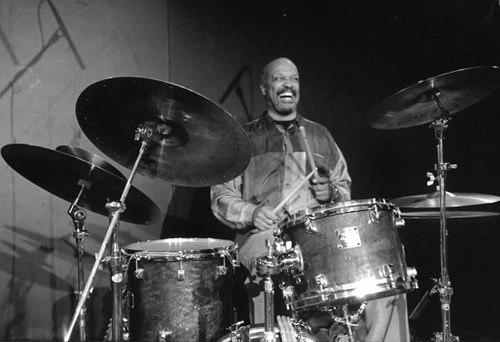

John Betsch © Jacky Lepage

I can't remember exactly how we met but several things stick out when I think of him. The first, of course being the spirit of his sound: so many saxophonists but so few with real identifiable spirit to their sound and Thomas always stuck out that way. We did gigs with bassist Mario Pavone in Connecticutt where Mario lived and a recording in New York with Ronnie Mathews, the late underrated pianist. I've lost track of Mario but he might actually have some recordings of our gigs together.... Thomas's joyous enthusiasm was infectious: I remember driving with him and Mario to a gig with Thomas raving in the back seat about all the different ways of playing and Mario and I delightfully amused!

It's very difficult to say in words the magic of Thomas's spirit but thankfully he left us with wonderful recordings and I'm very proud to have participated in one.

John Betsch

Ned Rothenberg © Caroline Forbes

It's common with creative artists to talk about the love they put into their work. This 'love' can mean many things - care, focus, commitment, curiosity. Thomas's musical voice had all these things but it also brought love in its most direct romantic sense. He was 'in love' with music and the vast realm of the sounds he could make and the sounds around him. This was so direct that it joined the idiomatic (jazz and the many other styles he mastered) with the universal (the joy of listening to nature and the human cacophony) so that, sophisticated as he was musically, a pure and tremendously attractive childlike wonder remained.

From the liner notes from the Double Band CD “Parting”:

… Thomas was a rare fellow, highly intelligent, full of arcane knowledge (“don’t be trying to help me with this crossword puzzle“), a searcher after all those unknowable truths, and yet beneath it all, not really an ‘intellectual’ in the conventional sense. He would always rather just do something than talk about or around it. Just like his playing, always direct, just what it was, the man singing, the pure improviser.

Ned Rothenberg

© Peggy Stern

… people ARE how they play. Thomas's music was fresh and pure, spontaneous and generous of spirit … He was a bundle of energy, all the time … So devastating was his torturous last few months and his death, because he was such a ‘live’ person – so fun, and silly, and serious, and just full of music and piss and vinegar …

Peggy Stern, pianist

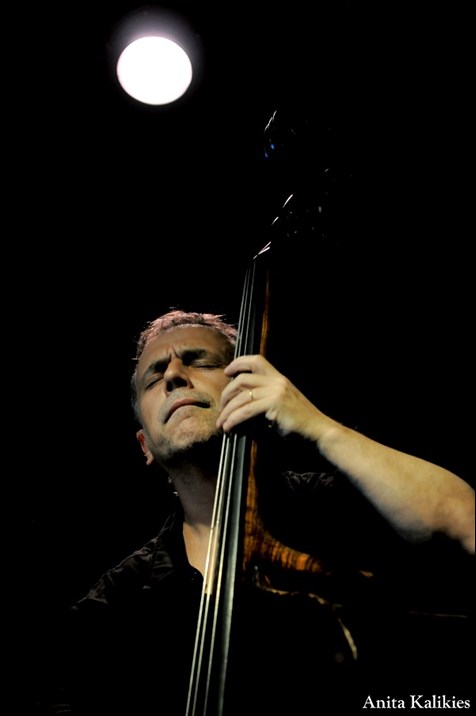

Pablo Aslan © Anita Kalikies

Thomas was monumental, as time goes by I grasp the enormity of his talent and spirit (and Stephanie Castillo’s film, Night Bird Song, was great help to understand him!). I was lucky to encounter him, he pushed my boundaries, or as we say in the music world, he kicked my ass!

Thomas remained voraciously interested in the musical language that I was introducing him to. He absorbed the phrasing style, and he discovered a way into this music from his own creative source as well. This appetite and this ability to turn the language around and make it his own was very inspiring. There was no question that he was right there with you every time you played. His commitment to making music was complete.

Pablo Aslan

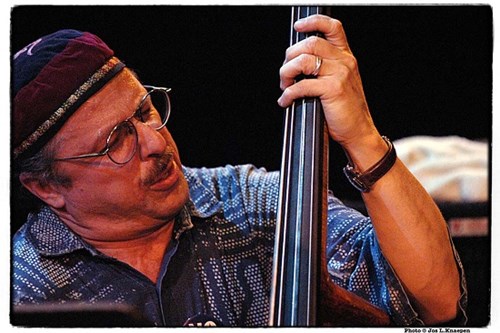

Steve Johns © Chris Drukker

The first time I recall meeting Thomas Chapin was at a Lionel Hampton audition at Carroll Studio’s in NYC around 1989. I don’t have much of a memory of the encounter except that Lionel kept knocking his Pepsi off his vibes with his mallet and Bill Titone his manager would replace it and Hamp would knock it off again. Thomas was leading the saxophone section and smiled a lot. Thomas was encouraging to me during my audition. I didn’t see Thomas again for a while until I got a frantic phone call from him one afternoon telling me that his drummer Pheeroan AkLaff wasn’t able to make the gig at the Knitting Factory that evening and asked if I would be able to make the gig. At this time in my life I was really trying to be a mainstream jazz drummer so Thomas’ music was everything but that and would be a real mind bending and challenging experience for me. I showed up to the Knitting Factory and met the great bassist Mario Pavone “now one of my dearest friends” for the very first time and we began to rehearse the compositions that we would play that evening. Right away from the very first note we had a vibe and I knew that this was going to be a great night. We played to an enthusiastic crowd and the Thomas Chapin trio was born! Later that year A&M Records released a compilation CD Called Live at The Knitting Factory Vol. 3 and one tune “Insomnia” from that very first gig with Thomas was chosen to be on the CD. I didn’t know that my first gig with Thomas had been recorded but there it was the very first official recording of the Thomas Chapin Trio!

Thomas was such a fun person to be around always cracking me up with things he was thinking about. But he had another side to him that was very serious and he was demanding of our attention at rehearsals having a very specific approach to composition “a task master” as Mario Pavone would always say.

As a result of this release of the “Live at the Knitting Factory” CD we started doing tours of Europe and Thomas’ trio was on its way.

Thomas Chapin was one of the finest musicians I’ve ever known. A true master of the saxophones, flute, various miscellaneous instruments and a very special person in my life. I will never forget him.

Gone way too soon.

Steve Johns, drummer

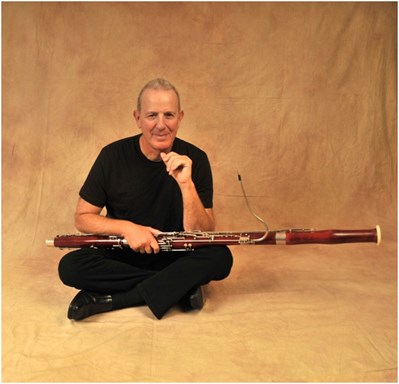

Peter McEachern © Steven Lashever

I still feel Thomas Chapin’s spirit in my life, hear his music, and laughter. Hanging with Thomas was always a high voltage experience whether on or off the bandstand. Thomas “was” music and wherever he found himself it became a musical experience. His palette was wide open, certainly the concert setting whether mainstream or avant garde, but also finding pipes that produced tones in an abandoned industrial site, or novelty instruments at toy stores. Thomas allowed me the space, to feel I could contribute to the moment and encouraged me along with countless others to develop my voice. I was also amazed not only by his musical abilities but by his sensitivity and support for all those around him. I often call on my memories of our many gigs and hangs to help inspire me. I feel fortunate to have played and recorded with him, and to have had many late night talks about music and other mysteries. We are lucky he left us with a body of recorded work so all can hear his brilliance, artistic integrity, and get a glimpse of this champion of the creative spirit. I am reminded of just how much I miss him as I write this.

Peter McEachern

Peter Madsen © Jacky Lepage

Thomas Chapin and I first met at my apartment in Brooklyn in the mid-80s through bassist Kiyoto Fujiwara. How lucky I am to have spent so much time together playing and talking and laughing with this wide-open musical genius! Thomas was truly one of the finest creative musicians I ever met in my life! He could have filled a stadium with his energy for music and the full spectrum of life! His love of everything to do with music and improvising effected everyone around him...including me. I'm sure in the years that he has been gone he has been busy inspiring the Gods with his joy and visions of a better world full of improvised music for everyone! I miss Thomas everyday!

Peter Madsen

Armen Donelian © Stephen Donelian

Thomas Chapin was my good friend for several years until his untimely passing in 1998. I met him, I believe, in 1987 or ’88 while performing at Visiones Jazz Club in New York City with Night Ark, a Middle Eastern Jazz fusion group led by oudist Ara Dinkjian with whom Thomas attended Hartt School of Music. Thomas approached me in the club and after speaking together for a few minutes we felt an immediate connection. We decided to get together to play, and soon we were doing gigs together, both in his bands and mine. In his bands, usually it was with Mario Pavone or Kyoto Fujiwara on bass and Steve Johns or Mike Sarin or Reggie Nicholson on drums.

What made playing with Thomas so special for me was the immediacy, passion and joy he exuded in every note, not to mention his utter technical mastery of not only the alto saxophone but also the flute, his first instrument. This places him, in my opinion, in a league with the very finest of Jazz flutists ever to have played that instrument.

On a personal level, I felt a kinship with Thomas that embraced non-musical interests in areas such as politics, philosophy, mysticism, meditation and world culture. When I suffered a traumatic injury to my hands in 1991 requiring surgery and an extended recuperation, Thomas was the only person who visited me during my convalescence to offer some cheer and laughs.

A highlight of our professional work together was a two-week tour of France as a member of Thomas’ quartet with Pavone and Sarin in 1991 shortly after my injury, including a concert in the Toulon Jazz Festival. Another highlight was a live 1992 recording of my quartet at Visiones with Thomas and bassist Calvin Hill and drummer Jeff Williams. This music was eventually released under the title Quartet Language on the Playscape label, and received glowing accolades.

I will always remember Thomas’ humor, humanity and kindness. The fact that he was a complete musician with whom I shared significant history only adds a sense of pride and accomplishment to the essential friendship and mutual respect underlying our collaborations.

Long Live Thomas!

Armen Donelian

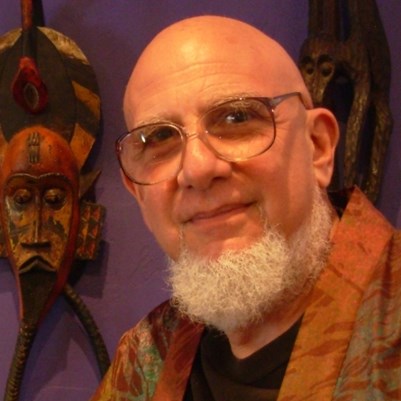

Ara Dinkjian © Kendall Messick

I first heard Thomas Chapin in 1976, as a freshman at Hartt School of Music. He was one of the soloists in the school’s jazz big band. I was not a fan of jazz at that time, but when Thomas stood up and played, something magical happened. His energy, freedom, unselfconsciousness, and sheer joy shattered all categories and subdivisions of music and art. I was so taken by his music that I did something I have rarely done: I went backstage to meet him. I told him how much I enjoyed his performance, and introduced myself as an oud (fretless middle-eastern lute) player. Although he was polite, I was left with the feeling that the jazz fraternity is an exclusive club!

Nonetheless I continued to follow and admire his progress, which eventually provided him the opportunity to travel around the world. A few years after our first meeting, to my utter surprise, he knocked on my apartment door, and asked if we could talk about world music! Soon after that, he began inviting me to play with him at his club gigs, concerts, and recordings.

Playing music with Thomas was both thrilling and intimidating, as he forced me to stretch my own limitations.

However, my most precious moments with Thomas were our countless hours talking, about everything. He was so curious and confused about life, and yet at the same time he was so sweet, generous, and child-like. Of course, this all came through loud and clear in his music.

There is nobody like him. I miss him. I’m so grateful to have experienced his magic.

Ara Dinkjian

Mark Dresser © Susan O’Connor jazzword.com

I personally liked and admired Thomas Chapin, though I had had no musical interaction with him. I became aware of him through his performances at the Knitting Factory and our mutual musicians friends, Ned Rothenberg and Michael Sarin. When I learned he was sick I visited him in the hospital and as I had a car I could offer to help out with some medical appointment. The connection was a predominantly a human one and recognition that Thomas was a warrior musician, virtuoso saxophonist, who could write memorable tunes and as a performer gave all at each gig with a level of virtuosity, energy and spirit. His demise was a real loss.

Mark Dresser

Joe Fonda © Jos L. Knaepen

I know Thomas from the scene in Hartford, Connecticut. I was living there and that's where he grew up. So we were playing at the 880 Jazz Club in Hartford together very often. We were in a few big bands together. He also participated in my Kaleidoscope Ensemble, that had a painter, a dancer, a sculpturer, an actor, a cook, and 4 musicians. They were doing their thing at the same time.

In January 1992 I joined Thomas Chapin at a two weeks tour in Spain. Carlo Morena was on piano, drummer was Fernando Llorca and Jorge Pardo played tenor and soprano saxophones and flute. I still have a tape from the gig in Zaragoza (Centro Civico Delicias, January 11th). That was quite a concert. As always, playing with Thomas was very energetic and very inspiring to me.

We were good friends.

Joe Fonda

My friendship with Thomas goes back to 1977, my freshman year at the Hartt School of Music in Connecticut. He was still called ’Tom’ then. He was two years older, and our birthdays were two days apart. We became friends immediately and he began to introduce me to players on the jazz scene in Hartford at that time. I often accompanied him to gigs. He played all kinds of music, including completely improvised concerts with Zasis, a collective with Thad Wheeler, Bill Sloat and Rob Kaplan. This group in particular had a profound effect on my musical understanding, and Thomas' personal aesthetic regarding music and sound was revelatory for me.

In the 1990’s, while I was living in Manhattan and Thomas was in Queens, he began studying with a spiritual teacher named Gil Barretto. Gil admired Thomas’ music and was a saxophonist himself. Gil later became my husband.

One day, long after Thomas had passed away, I realized it was he who first pointed the way. He showed me how it was possible to access the infinite realm of sound, like an Explorer, and bring back treasures from those journeys that you could share with others through your music.

Thomas did what he came here to do. I’m sure his life and music will continue to be inspirational for many musicians, and artists of all kinds.

Su Terry

© Courtesy Robert Kaplan

I first met Thomas in 1976 when looking for a practice room at Hartt School of Music. I heard someone playing the hell out of Giant Steps on piano. Through the window I saw a head of wild black hair, body swaying as he played…and I had thought he was a sax player! Each Sunday we would set up a huge array of instruments in Bliss Auditorium at Hartt and play for hours. We became a quartet called Zasis — Thomas on woodwinds, artillery shells, bird whistles and toys, Thad Wheeler on percussion, strings of wrenches, bundt pans, and a kitchen sink, Bill Sloat on double bass and electric bass, and me on acoustic and electric keyboards, tape recorders, and misc. percussion. Performances were totally improvised. Over the eight years we had developed ensemble thinking rehearsal strategies and compositional sense that served us all well.

In Thomas’ words: "Our music tells stories, paints pictures. It creates new worlds. You become a leader and a follower...If anything has given me spiritual enlightenment, or direction in music or helped my musical awareness, Zasis has been my source." - (Interview by Phil Tankel, Hartford Advocate, 1977)

Often we would finish playing a piece and we’d all wonder where that came from. Chapin would then shriek out laughing. These became known as Zasisizations.

In my last conversation with Thomas he had resigned himself to the fact that his survival was out of his control and in God's hands. Even then he kept saying that we have to do a CD. He emphatically yelled into the phone, "ZASIS LIVES!"

He’d be happy to see many of our techniques devised for rehearsals being used at Arizona State University in transdisciplinary improvisations.

So glad Thomas is coming back around in this way. I think of him so often.

Robert Kaplan

Vernon Frazer © Jonathan Duboff (Courtesy Vernon Frazer)

After hearing my first set of Thomas Chapin late in 1980, I asked myself, “Why isn’t this guy famous?” To my ears, Thomas was one of the most original and accomplished saxophonists to play in the 1980s and 1990s. Nobody I’ve heard since has equalled or surpassed him in skill or inventiveness. Thomas not only possessed a distinctive style; he possessed listening abilities that enabled him to blend with any musical situation in a protean manner while projecting his singular musical personality within the context of the performance. When he and I performed as a duo in the early 1990s, I never had to tell him what to play; his grasp of my poetry and his ear for music enabled him to play parts that sounded far better than any I could have created for him. He was one of the most complete musicians I ever heard. He was also a dear friend, whom I miss very much.

From the text from ‘Put Your Quartet In And Watch The Chicken Dance’ on “Menagerie Dreams”:

In the Houston Street performance space his fingers weave flute-sounds over the toe-dance that syncopates his beat.

Vernon Frazer, poet-bassist

Saul Rubin © Seth Cashman

Thomas Chapin was an incredible instrumentalist and composer. He stretched the boundaries of style and was enigmatic in that way. He really knew Jazz, meaning straight ahead jazz, but also embraced free jazz as well as Brazilian, Tango , Flamenco, Salsa, etc.

He played flute like no other and his alto sound was strong and unmistakably recognizable, an unusual thing in the days of clones and imitators. When he was playing strong it was with tremendous energy but his ballads would make anyone close to tears.

I knew Thomas from Hartt College of Music in 1976. He was way ahead of everyone on his instruments and conception. He later went on to Rutgers University. For a few years in the late 80's he had me in his band Spirits Rebellious. These compositions were very influenced by Brazilian music especially Hermeto Pascoal. After that group he went on to from his trio which was his primary group till the end of his life. He died way too young but left a great body of recordings and compositions. His sister in law's documentary film really captures Thomas as he was.

Original bassist and friend from Spirits Rebellious, Arthur Kell and I have recently started playing again as Spirits Rebellious , playing the original tunes Thomas wrote during that period. We are revisiting these great compositions with percussionist and original member Joe Cardello, drummer Mark Ferber and saxophonist Stacy Dillard. The band is different without Thomas but still very exciting.

Saul Rubin

Arthur Kell at Bar Lunatico in Brooklyn, NY © Skyler Smith

I met Thomas when we were fifteen and just students at a private school. From the first note, his playing knocked me out. Everyone at the school stood up and took notice and never forgot. He was astonishing — his connection to the music was already fully formed. For some reason we bonded deeply and it lasted a lifetime. We improvised into the night on anything and everything: standards, Stevie Wonder, free music. He was possessed even then.

Thomas had it all: heart, energy, sound, technique, concept, humbleness. He was a deeply thoughtful person, a deep well of sensitivity, on and off the bandstand. And his commitment to music was so innate and profound that anyone listening couldn’t help but hear it. Out flowed something spiritual, something with humility. The tremendous strength in his music derived from that foundation. And he could have so much fun with music that it infected you. There was an indescribable, piercing beauty to his playing. It was there as a teenager and it was there the last time he played. He was seventeen when he said to me: “Always create something with your music. Keep your original music happening. Always be creating.” That advice stayed with me all my life.

Arthur Kell

© Jennifer Van Sickle

Tom (Chap) as we called him in Connecticut where I met and heard him with Mario Pavone groups playing in Hartford and Waterbury was a constant source of inspiration to me. I marveled at the intensity of his playing both on alto and flute. He also brought any group he played with up a notch in terms of energy and creativity. His precocious curiosity of the world around informed and influenced his music profoundly. Our collaboration in the mid 80's playing regularly at the 55 Bar in Greenwich Village allowed me to respond to and be part of that "Chapin" energy and exploration. Playing with Tom was an exhilarating ride. One morning after an evening of intense playing I was compelled to call him because I felt I had to tell him how privileged I was to have taken this intimate musical journey with him. That feeling I had that morning is still fresh and as palpable 30 years later.

I loved Tom and blessed to have been there on the scene with him.

Michael Rabinowitz

Courtesy Adam J. Brenner

I first met Thomas Chapin when I got to Rutgers/Livingston College in 1978. I was really impressed with his playing and his sight reading skills. In the student big band led by Paul Jeffrey, we had a lot of very difficult music to play and Tom (I knew him as Tom) would always be reading through most of the parts right from the first time when the rest of us would be just hanging onto a few notes.

He was very passionate about music and his excitement and interest in all kinds of music was infectious and I loved his spirit. He and I would hang out socially and he turned me on to many artists I didn’t know about including people like Frank Strozier and Roland Kirk. I had heard of Roland, but didn’t really get into his music but Tom encouraged me to listen to everything without judgement.

I loved listening to Tom’s solos and especially loved his flute playing. He had a lot of interaction with alto saxophonist and flutist James Spaulding, who was one of Thomas’ primary influences at the time who was very much on the scene at Livingston.

Tom graduated a couple of years before I did and when I graduated, a couple of months later I joined the Lionel Hampton band and played next to Tom in the reed section until he left to begin a solo career in 1986. Tom quickly rose to prominence and it was gratifying to see his acceptance in both the straight-ahead and the so called “avant-garde” or free-jazz audiences. I know he was a one of a kind artists with tremendous abilities to incorporate all of his varied influences into a blend that was uniquely his own and had a true commitment to making music his way yet he reached people at a very deep level.

He didn’t give me much advice, but occasionally would say things that stuck with me and I knew he and I shared a great respect for each other’s playing. I know we won’t see anyone like Thomas Chapin ever again and I know his music will endure and even though his life was cut short in his prime, he left enough music with us to prove forever that he was a major creative force that set the bar extremely high for all of us to be inspired by and challenged by.

Adam J. Brenner

Thomas and Allen Won w/ Shunsuke Fuke on drums (CPhoto: courtesy Allen Won)

(Kiyoto Fujiwara, bass and Peter Madsen, piano also played at this Kiyoto gig.

I don’t know what I can say that has not already been said about Thomas Chapin. You have so many great musicians from his life recounting his accolades in spades. All I can say was that he influenced and inspired me and still does to this day. His music and his playing were some of the greatest and most memorable moments in my musical life and he helped nurture a passion for the pursuit of beauty in everything I do.

He was a renaissance man of a sort. In everything to do with music, in every object he found he saw the potential of a sound, a voice to make heard. And he would make it happen. I felt as though Thomas was creating history with what he composed and played. His influences and musical tastes were vast and yet he made it all seem so obvious and simple.

One of the times at the original Knitting Factory, I burst out laughing during Thomas’ set. Afterwards, I went to speak to Thomas and apologize for my out burst but Thomas looked at me with his characteristic smile and said, ‘no man, I dug it cause I knew you got it’.

It took me a good 15 years before I could speak of Thomas without breaking down.

His passing is still unbelievable to me but I accept it now. I still miss my friend.

Allen Won

Steve Dalachinsky & Yuko Otomo © Appoline Lasserre

Lines for TC

(trippin’ on Chapin)

Thomas Chapin: reed player / flutist / composer / visual artist / collagist / poet / mentsch / everyman \ renaissance man / musicians ‘s musician / warm heart true friend / whom i love & miss & think of every day >

Thomas Chapin: seeker / innovator / faithful forgiving formidable soul >

Thomas Chapin: the ears of music when the husks are stripped away /

the voice that resonates when the duet is in disjunctive harmony

bras(s)h sweet kernels

i speak to you as you speak to me

this sound we hear that is one in us all

& all the silence & all the taste & touch & scent & sight

that is all this very big/small WORLD

i could if i could play

music could if i could say

music would this way that way

the way the fingers dance

the way the singer takes a chance

&

i should

if i could & i would

if i could

play music

say music

be

music

see music that music would be you…

Steve Dalachinsky, poet

Thomas Chapin lives in us, not as a memory but actually as a wholesome existence, not just as a musician in a narrow sense of the labeling category, but as a cosmic total being. His angelic personality & his total dedication to what he loved were so genuine & enduring. Music; art; poetry; traveling & adventures… he loved everything life offered him & he loved people he encountered whether it was brief or more involved. We knew Thomas loved us & he knew we loved him. This type of total pure love & friendship does not happen too easily. The most amazing thing about Thomas was that he knew many people & everyone of us had identical reactions to his loving nature. The love between him & us was so real that no one had to claim or to declare it since it was always there in the most natural manner.

Yuko Otomo, poet

Quotes from Music Industry Colleagues and Friends:

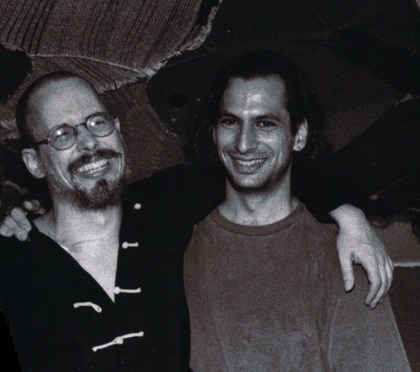

Thomas Chapin and Danny Melnick, Japan 1993

(Photo permission by Akasha, Inc.)

Thomas Chapin was a force of nature. He was wild, funny, smart, considerate and an incredible musician and composer. I LOVE his music and thought he was one of the most compelling live performing artists I have ever seen. I had the honor of presenting him in Newport, New York City, Japan and other places. For me, and many others, he stood at the center of numerous disparate worlds of jazz at that time. He was a master of all forms of jazz and maybe proved that these "schools" or "styles" weren't so different at all. He left us way too soon and for those who knew him, saw him play and know his music, he will be with us forever.

Danny Melnick

President - Absolutely Live Entertainment

Danny Melnick is a festival, tour and concert producer and at the time was working with George Wein's Festival Productions, Inc. Danny was one of the people who booked Thomas at some of the larger festivals for the first time. Danny knew that Thomas belonged on the big stages such as the Newport Jazz Festival, the Madarao, Japan Festival and the JVC Jazz Festival in NYC.

Bruce Lee Gallanter © Courtesy Downtown Music Gallery

I met Thomas Chapin in the mid-1980’s when a poet friend of mine named John Richey organized a band with former students from the Rutgers Livingston Jazz School in New Brunswick, NJ. A guitarist named Bob Musso picked four of his favorite musicians from the school, adding John Richey to sample radio, TV & tapes, as well as spoken word cut-ups. I had already known about Thomas Chapin after witnessing him play with the student jazz ensemble a few years earlier, playing one short solo amongst more than a dozen student saxists and blowing everyone away. The band was called Machine Gun which seemed most appropriate since their sets were an assault on the senses. Combining the best elements of free jazz/rock/punk/funk with Thomas’s alto sax screaming and pushing them higher and higher. Bob Musso soon started a label called MuWorks which I volunteered for. MuWorks released an early Thomas Chapin record called “Radius”, which I wrote the liner notes for and which remains one of the undiscovered gems of modern jazz. Mr. Chapin put together a trio in the early nineties with Mario Pavone and Steve Johns, which became one of the hottest and most inventive bands to emerge from the Downtown Scene. That scene was centered in a small club called the Knitting Factory on Houston in NYC. The Thomas Chapin Trio never ceased to amaze all who heard them so I was happy to help them get gigs. I got them a great slot opening for a John Zorn electric trio at the Knit which won them a new and devoted following, a month later they were signed to the new Knit Works label, which went on to release seven of their CDs, all wonderful! The Knit (Knitting Factory) also organized European tours for some of their artists so Thomas’s Trio gained an international audience as their fame grew. Each of those seven trio CDs are great with Thomas adding a horn section on one and a string section on another disc. I tried not to miss any performance that Thomas made since every one was special. he always gave his best and uplifted those in attendance. There is a clip of the Thomas Chapin Trio at the Newport Jazz Festival that captures them at their best. If you haven’t seen it, please do check it out - it is just incredible!

I keep a large picture of Thomas Chapin on display at my record store Downtown Music Gallery in Chinatown, NYC. Folks often ask who it is and if we are related and I am only too happy to talk about him and play his music in the store. Thomas passed away from leukemia in 1998, he was way too young, only 40 at the time. His music and his spirit continue to inspire those who knew him when he was alive and those who have discovered him after his passing.

Bruce Lee Gallanter

Co-Manager & Co-Owner, Downtown Music Gallery, NYC

Bruce Lee Gallanter founded Downtown Music Gallery in May of 1991, and for over 25 years DMG has promoted all forms of New Music: Avant Jazz, Progressive Rock, Modern Composer and Downtown Scene Experimental sounds.

Marty Khan © Helene Cann

Thomas Chapin is a profound manifestation of the traditional values, ancient wisdom and pursuit of Transcendence that have always been the true legacy of jazz. Sublime artistry, unique musical vision and unbridled passion were his hallmarks, but his warmly sincere humanism and deep spirituality made him an utter joy to know. It’s often said of some special people, “to know him is to love him.” Thomas was the embodiment of that concept.

Marty Khan

Friend and occasional advisor to Thomas, Marty was a longtime manager for artists such as The Art Ensemble of Chicago, George Russell, Sam Rivers, John Zorn, World Saxophone Quartet, Sonny Fortune and others from 1976-2000. Today he is an author and a strategic planner/management advisor for a number of artists and non-profits. www.outwardvisions.com

Enid Farber © Courtesy Akasha, Inc.

Thomas Chapin was not so much a "colleague" as a frequent subject of my lens, a favorite and preferred one at that. Thomas was rare in the milieu of jazz men whom I pointed my cameras at, in that he afforded me the greatest respect and never ever showed displeasure, attitude or sexist shun towards me. In fact, he demonstrated gratitude and acceptance and understanding that my role in contributing to the lexicon of jazz history was as valid as any member of his band. Each time I photographed him he accomplished something that was precious and all too rare for me, that being his spirit was so welcoming, his heart so full of love and respect for the audience and I felt the same generosity and acceptance towards me. Not all in his world of music have extended the same kindness towards me and I am always going to remember that with profound gratitude.

My memory of his playing is mostly the joyousness that I felt emanating from the stage and Thomas' horn. His relative obscurity at that time was eclipsed by the magnanimity of his personality!

Enid Farber

Enid Farber is considered one of the world's top jazz photographers. Farber and her work were featured in Jazztimes Magazine's December 1997 "Classic Jazz Photography" issue as one of the masters of jazz photography. She was the sole female of four names mentioned in the New York Times in May 1997 as "one of the young generation of talented photographers documenting the current jazz scene". Some of Farber's classic jazz images were selected for noted filmmaker Ken Burns' historic 20-hour documentary on jazz aired on PBS in January 2001 and its companion book. In the 20th anniversary issue of Jazziz Magazine, the editors said, "If we were to identify a JAZZIZ visual historian, her name would no doubt be Enid Farber. For longer than a decade, her photography has taken readers on an odyssey, to experience the most adventurous music & to meet the most interesting personalities, from both the new and traditional worlds of jazz".

Thomas and Sam Kaufman © Enid Farber

(Photo permission by Akasha, Inc.)

It was a privilege to know and work with Thomas Chapin who left such an important and lasting musical legacy. Thomas had a unique view of the world that allowed him to see and hear things that other people could not. His insights and observations came out, not just through his music, but through everything he did in life. Just being in the same room or space with Thomas had a way of opening you up to new possibilities. I’ll never forget seeing Thomas when I was in Amsterdam and at the North Sea Jazz Festival. The festival had so many bands playing simultaneously but Thomas’s sound cut through everything and drew me right in. Never satisfied to remain on stage, he would stroll among the audience with his wireless mic and find individual connections with audience members. For anyone new to Thomas’s music, I would highly recommend listening to the opening track on Anima. Thomas had an energy and spirit that lives on today and belongs to the canon of great jazz -- and music in general.

Sam Kaufman

Sam Kaufman was Thomas Chapin’s friend and agent/manager during the last year of his life. He now runs a partnership marketing agency where he works as an agent for brands such as Bloomingdale’s, Hugo Boss and Canon.

Teresita Castillo © Jos Demol

from Terri Castillo Chapin, NYC:

It's gratifying to see the force of Thomas Chapin and the power of his music still inspires and continues to generate high interest and relevancy among new listeners, musicians, including younger, next-generation players, and the general public since his passing in 1998.

For those of us who knew him, who played with him and who saw him perform live, it is no surprise, as Thomas was an original, "the real deal" as international saxophonist John Zorn has said. Thomas himself explained it: "Music was never something I had to consider, it is my state of being."

Now, the new documentary, "Thomas Chapin, Night Bird Song" by Emmy-winning filmmaker Stephanie J. Castillo, captures and celebrates his deep spirit as a human being and as one of the great players in jazz who left us too soon at age 40. When Thomas passed 18 years ago, critics told me, "Thomas will only get more known as the years pass. He will always be discovered by new audiences because people are always looking for quality, and that is what Thomas was about."

This has proven to be true. He is Alive--in the music, in our hearts. And in new hearts.

Photo permission by Akasha, Inc.

Chapin pushed his saxophones and flute to the bursting point, squeezing out colors and manic, joyous figures in a high-energy performance with his trio Friday night at Hartford’s 880 Club. Under his fleet fingertips, he has the whole free jazz reed tradition of Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy and Albert Ayler. But the tumultuous free jazz spirit of the 1960s is merely a launching pad for his ascensions.

Owen McNally, Hartford Courant, 1994

Like one of his main musical inspirations, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Chapin approached live performances with an extroverted sense of theater. Also, like Kirk, Chapin’s mastery of his instruments, particularly alto saxophone and flutes, were provocative on their own terms. He was a monstrous saxophonist, and certainly one of this generation’s flute masters.

Larry Blumenfeld, JAZZIZ, 1998

Chapin… is a virtuoso… also one of the more schooled musicians in jazz, both technically and historically, and for his set he dug into the styles of everyone from Benny Carter to the 60’s avant-gardists, screeching and howling and huffing as if this were 1964 and he was breaking the rules of jazz into pieces.

Peter Watrous, The New York Times, 1995

Chapin was a study in the testing and exceeding of limits. In every live set and on every recording, he plunged headlong into the musical abyss and responded with a driven yet upbeat concept that held humor, cataclysm and contemplation in rare equilibrium. The sound tapestries that resulted – solidly rooted in a tradition Chapin knew intimately, yet straining that tradition’s boundaries at every turn – were both lucid and combustible. They remain just as inspiring now that Chapin is gone. ‘The point is to stay awake and alive to what is going on,’ he wrote in 1996; and the sounds Chapin left assure that he continues to be a living force."

Bob Blumenthal, Boston Globe, 1999