LICHTSPIELE

of eminent cineast Sergej Parajanov (1926-1990)

A trigger and continuous inspiration

for the creation of present music

The ‘Lichtspiele’ of his SHADOWS OF FORGOTTEN ANCESTORS (1965) with its deep digs into ancient indigenous folk sources of the Hutsul people in the Carpathian mountain area were and still are a trigger and continuous rich inspiration for the creation of genuine culturally loaded and lively ambient music for Ukrainian 3unit of Maryana Golovchenko (vocals, ancient Ukrainian folk instruments, electronics), Anna Antipova (violin, percussion, electronics) and Kateryna Ziabliuk (piano, percussion, spoken word). They realised a captivating journey with a profound, deeply moving effect in their concert performance at The Hague’s Paleiskerk on Saturday night, January 24, 2026, a performance that has been and is still growing in depth and width. I had seen their workout two times before since November 2022, at Jazzfest Berlin and at the Music Meeting Nijmegen and their program is still growing.

Berlin 2022

"It revealed a kind of deep ambient imbued by a touching fervour for the cultural richness and identity - a kind of out-of-time vibration and flow ..” (Henning Bolte, Jazz’halo)

Nijmegen 2023

"Most impressing of the appearances was the (…) elevating and celebrating Paradjanov’s poetic cinematography from the past. While the moving pictures, sometimes in its dynamics creatively blurred, had no chronological story line, but highlighted moments of subjective inner experiencing alternating with mystical imagery of a higher spiritual layer, the musicians succeeded, to let emerge a significant narrative, taking shape and get it deeply embossed in beholder’s soul. It was much more than just a new soundtrack by this famous film work from the past. It was a collage of footage from Paradjanov’s movie, landscape pictures and the celebrating music created by the trio in honour to the magical moving pictures. The three musicians made something up from diverse elements that stayed with you. They showed great mutual understanding, great rapport in their playing thereby drawing the audience deep into the unfolding music and generated a gentle and beautiful work of art of their/its own.” (Henning Bolte/Stanka Hrastelj – Jazz’halo)

I also had the luck to watch Parajanov’s film last year in an Amsterdam cinema (Rialto) as part of a selection of cinematic masterpieces made by Martin Scorcese. In looking back on the Paleiskerk-concert. I give a bit context on the inspiring artist, Sergej Parajanov.

Cinematic opus as focal point

Parajanov’s wild poetic images of “Shadows …” function as lasting strong focal point of original Ukrainian cultural identity also brought to creational life in the musical work of Maryana Golovchenko, Anna Antipova and Kateryna Ziabliuk as an act of culturally grounded artistic self-assertion of resounding impact.

Their work is a reversal of the conventional relationship of film and music. They do not create a new score for Parajanov’s masterpiece. They use the wild poetic images and the indigenous cultural basis of the film based on the Carpathian ancient Hutsul culture including its folk music sources as a trigger and guideline for an original standing alone work where ancient folk music sources enter a new radical and strong symbiosis with present sound realms. Recreation has not been done this way before but actually it is not so surprising to rely on Parajanov’s material and use it as guideline and inspiration for own recreation especially considering that Parajanov was a trained musician and his films have musical traits.

Folk music as mother of all music

Folk music, the mother of ALL music, can be translated and transformed in many ways, in original, raw authentic ways, in softening folksy ways, in classical style, in ‘modernised’ style or in adulterating manner as in turbo-folk etc.. Golovchenko/Antipova/Ziabliuk followed in all development stadia of their recreation the ‘raw route’ of projecting their own ideas into the past and the future and let that reflect in both directions. It is an approach and process used especially in music from Armenia, for example in the case of the music of Gurdjieff by the Gurdjieff Folk Instruments Ensemble. There are a lot of ways to transfigure older folk music sources to our present listening.

Armenian artist Sergej Parajanov’s relation with Ukraine

His film “The Colour of Pommegranates/Sayat Nova” (1969), a film on the legendary Armenian poet-musician Sayat Nova is considered one of the 10 most important cinematic masterpieces of the last century. “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors” his first masterpiece in his typical ‘wild’ style preceded it in 1965 and was made in Ukraine, shot in the remote area of the ancient Hutsuli tribe in the Carpathian mountains in South Ukraine based on the 1911 novel of Ukrainian writer Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky (1864-1913) of the same title.

Parajanov himself was born in Tbilisi in 1924 as son of Josif Parajanian and Siranoush Bejanov (*). He undoubtedly led a turbulent life with extended periods of politically motivated rejection of film projects, and repeated imprisonment, which made it hard to realise his art. Nevertheless, he created a whole series of extraordinary, admired masterpieces. Reading his biography, one might get the impression that the massive opposing forces at work made him even stronger.

He studied violin, singing and dance before he entered the famous VGIK film school in Moscow where his main teacher was the Ukrainian Olexandr Dovzhenko (1894-1956). Dovzhenko played a prominent role in the pioneering Ukrainian and Soviet film world. He was a mentor of the two young filmmakers Larisa Shepitko and Sergej Parajanov.

1951 Parajanov married Nigyar Kerimova, a Tatar woman. She was killed by her family for marrying outside her family religion. After that tragedy Parajanov married Svetlana Sherbatiuk in 1955, a Ukrainian woman. He was asked by Dovzhenko to work at the Ukrainian film institute. He settled in Kyiv where he worked from the film production studios in Kyiv during the hole next decade and made a series of films among which finally in 1964 “The Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors”, his first masterpiece and an internationally acclaimed cornerstone of Ukrainian cinema.

Sergei Parajanov

The making and impact of “The Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors”

An important impulse for Parajanov’s burgeoning unconventional cinematic art, which 1964 culminated in the production of “The Shadows of Forgotten Answers”, was the creation and release of the film “Ivan’s Childhood” (1962), the first work of the other famous SU-filmmaker from that era, Andrej Tarkovsky (1932-1986). It induced an artistic wake up and encouragement to go for own innovative aesthetics.

Parajanov shot the film “The shadows …” in Kryvorivnia, a remote place in the Hutsul tribe area in the Carpathian mountains in the Ukrainian Hutsul dialect. The culture of the Hutsul people had already earlier got attention in Ukranian literature and composed music. Parajanov adapted the 1911 novel of the same title by Ukrainian writer Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky (1864-1913) for the film script. In the period from 1909-1911 Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky visited Capri and Greece and stayed himself in the Hutul area, which brought him to write his Hutsul novel. The score of the film was composed by Myroslav Skoryk (1938-2020), a central figure in the music life of Ukraine. “Hutsul Triptych” was the first of the 40 film scores he wrote. A few years before in 1959 he already wrote a “Carpathian Rhapsody For Clarinet And Piano” and after the film score in 1965 he continued the line with his “Carpathian Concerto For Symphony Orchestra” in 1972.

An example of a Hutsul folksong you can listen to HERE.

The 97 minutes film, also known under the title “Wild Horses Of Fire” has not only a strong significance due its anchoring in the ancient Hutsul culture in the Carpathian and its special ‘swirling’ ecstatic narrative style, ‘free camera work and non-linear narrative style, but also due to Parajanov’s insistence on the film’s original spoken Hutsul dialect and his refusal of dubbing it as usual in that time in Russian. The openness, authenticity and bold, deeply moving poetical nature of Parajanov’s work stood in stark contrast to pre-calculated artistic messages serving desired image formation of the Socialistic Realism doctrine in the arts of those days. Parajanov’s work opened too many emotional and mental floodgates what undesirable and had to be prevented. Its screening lead to turbulent meetings and heavy conflicts in Kyiv around cultural and national identity questions.

It had serious consequences for Parajanov’s working conditions. Further film projects received no support, were put on hold, or were abandoned. That included his project “Kiev Frescos”. This stood in stark contrast to the admiration and recognition his work received from his peers and the cinema world internationally. However, this was not only due to the rise of Parajanov's art, but also an expression of the deteriorating artistic climate in the beginning of the Brezhnev era (1964-1982) with its significant increase in repression and censorship throughout the Soviet Union after the Thaw and relatively liberal years under Khrushchev (**) after Stalin’s death 1955.

After finishing his film “Andrej Roeblov” on the 15th century icon painter in 1966, Tarkovsky faced similar serious difficulties in his film work until 1971. Tarkovsky had to recut “Andrej Roeblov” several times. It became accessible in a cut version under restrictive conditions in the SU in 1971. 1973-74 he worked on “Mirror”. It became a low categorisation that made it inaccessible for many viewers. 1976 Tarkovsky began to work on the famous “Stalker”, his last film made in the SU, completed in 1979.

Parajanov’s further path: arrests, artistic highlight, suppression, international acclaim

After the Kyiv tumults Parajanov was invited to Armenia to make a film on the multilingual/multicultural Armenian ashugh/bard Sayat Nova (1712-1795), which became his most famous and impressive film with the music of the then young Armenian composer Tigran Mansurian (1939). The film was finished in 1969 and also this film's reception history was thorny. The film got caught in the gears of cultural bureaucracy and censorship authorities. The same pattern repeated. It got a less outspoken title - “Sayat Nova” was changed to “The colour of pomegranates” - was cut, got no distribution and screening was allowed only under heavily restricted conditions.(***) So, his experience was similar to Tarkovsky's with “Andrej Roeblov”.

Arrests and prison stays were a recurring theme in Parajanov’s life. In 1948 he spent 10 months in prison (because of a homosexuality charge, which was illegal then). After his experiences with “Shadows of Lost Ancestors” and “Sayat Nova”, he gave a furious speech in Minsk in 1973 on the oppressing, ruining practices in the arts through the states institutions. It led to his arrest and in 1974 he was sentenced to five years prison in Ukraine. He was finally released in 1977 after international protests and intercession of the poet Louis Aragon, a French communist.

He returned to Tbilissi in 1978 but could not work on film projects. He dealt in antiques and made a lot of collages. In 1982 he was again arrested for bribery and spent another 10 months in prison, which caused a heavy attack on his health. Then he was released prematurely from prison after having been declared not guilty. After that - also with the impending political changes - his working situation clearly improved. Between 1984 and 1988 - the Glasnost period under Gorbachev from 1985 on - he could direct three films. 1985 the first exhibition of his artwork took place in Tbilissi.

Films he made, were:

“The Legend of Suram Fortress” (1984) - a Georgian story

“Ashik Kerib” (1988) dedicated to Tarkovsky - an Azeri story

The Confession (1989), unfinished - an autobiographical work

He could travel to festivals in Europe, a.o. Rotterdam (see the Youtube link to a long lively conversation with Parajanov in Rotterdam in 1988) and prepare new cinematic projects, which however could not all be realised by himself. Parajanov died in 1990.

Parajanov meeting in Rotterdam (1988):

After this tour de force finally however, four countries see themselves now as a breeding ground for his artistic work: Armenia, Ukraine, Georgia, Russia and even in the end Azerbaijan contributed. Parajanov was laid to rest at Armenian’s Pantheon in the company of Komitas, Khachaturian and William Sayoran. Parajanov’s radiance and relevance has not ceased, on the contrary, as the project of Golovchenko/Antipova/Ziabliuk shows. Through his art Parajanov has revealed and made tangible the core of various cultures beyond nationalist and other ideologies, thus contributing to genuine dynamic identity formation (HERE BELOW you can find a lively elegant and excellent talk of Nouritza Matossian over Parajanov’s life - it starts round 10 minutes after the greetings). His case and that of Tarkovsky, two clearly different characters, shows that original artists in the SU were subjected to far harsher challenges and had a harder life than artists in the ‘Western’ world.

Unravelling Sergei Parajanov's Masterpiece: The Colour of Pomegranates - Talk by Nouritza Matossian :

Sergei Parajanov – Parajanov-Vartanov Institute

Text and photos © Henning Bolte

Notes:

(*) Armenians had to russify their family name in those days.

(**) Breshnev (1906-1982) was a protégé of Khrushchev (1894-1971) but also ensured that Khrushchev was ousted. Both, Khrushchev and Breshnev were originating from Ukraine.

(***) In the SU films were classified by the censorship authority. Depending on the classification they had to be revised, got a/no distribution (also to foreign countries), were allowed for screening only to strictly selected groups.

Other

In case you LIKE us, please click here:

Foto © Leentje Arnouts

"WAGON JAZZ"

cycle d’interviews réalisées

par Georges Tonla Briquet

our partners:

Hotel-Brasserie

Markt 2 - 8820 TORHOUT

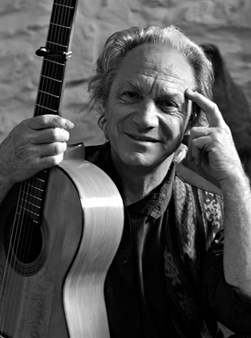

Silvère Mansis

(10.9.1944 - 22.4.2018)

foto © Dirck Brysse

Rik Bevernage

(19.4.1954 - 6.3.2018)

foto © Stefe Jiroflée

Philippe Schoonbrood

(24.5.1957-30.5.2020)

foto © Dominique Houcmant

Claude Loxhay

(18.2.1947 – 2.11.2023)

foto © Marie Gilon

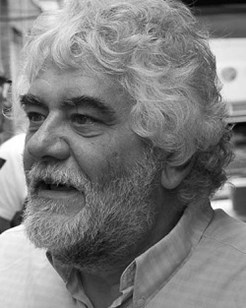

Pedro Soler

(8.6.1938 – 3.8.2024)

foto © Jacky Lepage

Sheila Jordan

(18.11.1928 – 11.8.2025)

foto © Jacky Lepage

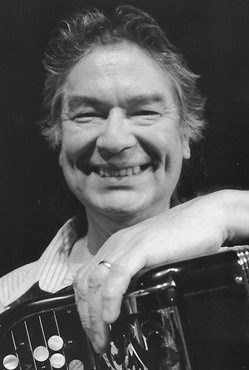

Raúl Barboza

(22.5.1938 - 27.8.2025)

foto © Jacky Lepage

Special thanks to our photographers:

Petra Beckers

Ron Beenen

Annie Boedt

Klaas Boelen

Henning Bolte

Serge Braem

Cedric Craps

Luca A. d'Agostino

Christian Deblanc

Philippe De Cleen

Paul De Cloedt

Cindy De Kuyper

Koen Deleu

Ferdinand Dupuis-Panther

Anne Fishburn

Federico Garcia

Jeroen Goddemaer

Robert Hansenne

Serge Heimlich

Dominique Houcmant

Stefe Jiroflée

Herman Klaassen

Philippe Klein

Jos L. Knaepen

Tom Leentjes

Hugo Lefèvre

Jacky Lepage

Olivier Lestoquoit

Eric Malfait

Simas Martinonis

Nina Contini Melis

Anne Panther

France Paquay

Francesca Patella

Quentin Perot

Jean-Jacques Pussiau

Arnold Reyngoudt

Jean Schoubs

Willy Schuyten

Frank Tafuri

Jean-Pierre Tillaert

Tom Vanbesien

Jef Vandebroek

Geert Vandepoele

Guy Van de Poel

Cees van de Ven

Donata van de Ven

Harry van Kesteren

Geert Vanoverschelde

Roger Vantilt

Patrick Van Vlerken

Marie-Anne Ver Eecke

Karine Vergauwen

Frank Verlinden

Jan Vernieuwe

Anders Vranken

Didier Wagner

and to our writers:

Mischa Andriessen

Robin Arends

Marleen Arnouts

Werner Barth

José Bedeur

Henning Bolte

Paul Braem

Erik Carrette

Danny De Bock

Denis Desassis

Pierre Dulieu

Ferdinand Dupuis-Panther

Federico Garcia

Paul Godderis

Stephen Godsall

Jean-Pierre Goffin

Claudy Jalet

Chris Joris

Bernard Lefèvre

Mathilde Löffler

Claude Loxhay

Ieva Pakalniškytė

Anne Panther

Etienne Payen

Quentin Perot

Jacques Prouvost

Jempi Samyn

Renato Sclaunich

Yves « JB » Tassin

Herman te Loo

Eric Therer

Georges Tonla Briquet

Henri Vandenberghe

Peter Van De Vijvere

Iwein Van Malderen

Jan Van Stichel

Olivier Verhelst