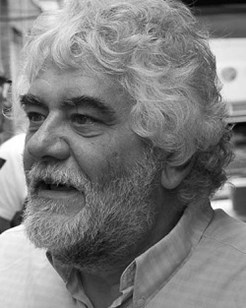

Lucian Ban – interview with the jazz piano player from Cluj (Klausenburg), Romania who is based since 1999 in New York, USA

I met Lucian Ban just before his planned concert at the Black Box (cuba, Münster). It was the start of a tour through Europe accompanied by Mat Maneri (viola).

So far I interviewed quite a range of Jazz musicians. A certain percentage was lucky to be raised by parents who were open minded, Jazz lovers or musicians. Do you think that is important to start a career in the Jazz world and why? In other words is it essential that your parents are open minded, Jazz lovers or musicians to start as son or daughter a career in the Jazz world?

LB: It certainly helps. I think if you grow up in an environment where Jazz is all around it certainly helps. I wasn't born in an environment in Transylvania where Jazz was all around but my father kept a great collection of music. Let's put it that way: Rhythm and Blues, Muddy Waters, all the stuff from the 60s. That introduced me to the American feeling and Blues. I learnt about Jazz a little bit later through a sort of mentor who was actually very knowledgeable. He had a huge collection and was one of the great experts in Jazz in Eastern Europe.

Did your parents helped you to express yourself in music and did they support you to develop your talent and skills by financing e.g. piano lessons?

LB: I was born in Transylvania, in a city in the midst of Transylvania named Cluj. I was born during communism. Jazz was not really a career under the regime of Ceausescu. There was some Jazz but it was underground. It was like a strange animal. You could not have a career as a Jazz musician in communist Romania. It was a music looked upon. This was actually a fascinating thing because it provided a gate of freedom for a lot of people. There were two festivals in the whole country. There weren't any clubs or festivals or circuits where you could learn about Jazz or teach Jazz. For the time I was around and started to realise what's going on from the age of 13, 14 to the age of 20 the time when the regime collapsed in 1989 it provided a breath of freedom for us. It was really fascinating and it was very important for me. My parents supported me but they knew at the same time that being a jazz musician in communist Romania is not a career.

How did you get in touch with Jazz and which kind of Jazz did you listen to?

LB: This I can answer specifically: My first ever album I encountered Jazz is an album by a South African pianist and an Argentinian saxophonist. The Album is called “Hamba Kahle” by Dollar Brand (Abdullah Ibrahim) and Gato Barbieri. It is still the ONE greatest album from this era for me because it combines the earthiness and south african thing with the free passion of Gato Barbieri. That was my first Jazz album ever and then I started to get into Jazz seriously.

You attended the Bucarest Music Academy and the New School in New York. Do you see any difference in the methods of teaching and considering the focus on certain styles of Jazz taught in one institute and the other?

LB: Completely different. You could perhaps say a hundred and eighty degree. The Jazz program in Bucarest was in its very early stages. It was after the regime fell. It was the first program maybe two or three years old as opposed to the one in New York which had decades of experience. I only wanted to go to New York and to the New School because amazing jazz musicians were teaching there. Reggie Workman, Charles Tolliver, Junior Mance, Phil Markowitz were some of the few I had the chance to study with. It was not only the method but the breath and the substance was tremendously compared to the program in Bucarest.

Do you think that the European Jazz or Jazz in Europe has stronger links to classical music from Bach to Berg than the Afroamerican Jazz?

LB: This is funny because since I moved to New York people try to make a connection the way I play, between my music and classical European music. First of all it is a geographical aspect. Classical music from the Renaissance to Bach to the 20th century music was born and developed in Europe. Obviously I was influenced by it. A lot of European musicians were influenced by this but at the same time European classical music & harmonic system influenced Jazz and American music. And then of course European Jazz musicians are influenced by American Jazz. I think jazz is one of the few music genres that can absorb almost everything and still retains some qualities that makes it uniquely Jazz. Rhythm is the definitive word here.

Did those connections you just explained affect you as far as your way of composing is concerned?

LB: Yes definitely! I had the chance to study with one of the great European classical composers by the name of Anatol Vieru. He was a student of Prokovief and died in 1998. I studied composition with him. I went through the whole canon: fugues, sonatas … but I was fascinated and in love with Jazz. From the very beginning I wanted to break away from the European influences. I was obsessed with this. Deliberately I wanted to shed away these influences. Maybe because I was drawn to certain Jazz musicians more: Monk, Abdullah Ibrahim, Andrew Hill, Paul Bley, Randy Weston. Some of them are very, very Afrocentric like Randy Weston. Andrew Hill is so modern. He also started with Hindemith in Chicago. Yes, to answer it short: It influenced me but I fought against it.

The Romanian-American Jazz Suite (Jazzaway Records) is a record you released. Could you tell me a bit more about the ideas behind the suite and the character of the tunes please?

LB: Wow, that's an older record. That was done with a sextet in 2008. Sam Newsome, one of the greatest contemporary sax players, was co-leader on the project. What happened is that we took a book of Romanian folk songs, carols, etc collected by an ethnomusicologist and Sam arranged some songs. I didn't want to arrange them. I was a very hardcore expat jazz musician living in NY. Sam arranged all the songs I knew from my childhood and we rehearsed them. I said: 'Wait a minute I wanna do some too.' It ended up that we both arranged songs probably almost half and half. Maybe he did a bit more. That was how that album came about. We had Alex Harding on baritone saxophone, Mat Maneri on viola and Willard Dyson on drums and I invited two musician from Romania: Arthur Balogh (bass) and Sorin Romanescu (guitar).

You performed with your octet in 2009 at the Enescu Festival in Bucarest. You played compositions by the Romanian composer George Enescu who wrote pieces in the tradition of Neo-baroque and Romanticism as I would see it.

LB: No, that is not fully correct. He was essentially a 20th century composer but didn't write neo-baroque compositions. He wasn't like Schoenberg but more like Stravinsky doing a very personal synthesis of Romanian folk music and late 19th century Wagnerian music. He wasn't a serialist like Schönberg or Webern.

What was the challenge for you to approach such type of music?

LB: First of all George Enescu is THE greatest classical Romanian composer and one of the great composers of the 20th century period. He was more famous in the world as one of the greatest violinists in last century. He was as well the mentor and professor for the young Yehudi Menuhin. Lots of people from Pablo Casals to Ravel to Menuhin called him a genius and I think they were right.

He toured the United States from 1923 to 1951 every year and remains known as one of the greatest violinists and conductors of the XX century. He was nominated to get the New York Philharmonic directorship. Enescu played piano, violin, cello, etc. Ravel said about him: 'If for some reason we would loose Bach's violin music that's not a problem. Enescu can write them out all from memory.'

He was a prodigy and actually wrote amazing music that is not as Avant-garde as Schönberg or Webern. His music was nevertheless fascinating. How I got involved with him? Enescu Festival, a one month classical festival extravaganza in Bucharest asked me to reinterpret his music from a Jazz perspective. So what I did I talked to an old collaborator the bass player John Hébert and told him let's do this together and let's figure out what kind of band we wanna have. First we choose the musicians. We knew it should be an octet and we had some of the best musicians at that time working in New York: Ralph Alessi (trumpet), Tony Malaby (sax), Gerald Cleaver (drums), Mat Maneri (viola) – that is how I met Mat – Albrecht Maurer (violin) along with John Hébert (bass) and myself piano and doing re-orchestrations of Enescu works.

To attenuate this heavy and brainy band we got I also invited the great Badal Roy on tabla and percussion. Badal is one of the most soulful musicians who has worked with Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman, Pharoah Sanders and many others. He brought a great earthiness to our Enesco Re-Imagined project. We took Enescu's pieces, from sonatas to orchestral suites, piano pieces to string works and symphonies just "re-imagined" them for this crazy downtown New York band. It became an extraordinary project, got lots of awards and amazing press and we toured For several tears festivals and venues in Europe and America.

Just let us talk about “Not That Kind of Blues”. Does that refers in one or the other way to Miles Davis “Kind of Blue” or do you mock Miles?

LB: No, it is actually a reference to Sun Ra.

When you started to compose this tune what was in your mind then?

LB: I had in mind the blues. I always mess with the forms and try to make them a little bit different for my ears. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn't. On this one it worked. It although worked because of Mat Maneri.

Let's talk about you and Elevation I mean your quartet. The album “Songs from Afar” was released by Sunnyside in Jan 2016 . It contains three pieces referring to Transylvania including the Transylvanian Sorrow Song. Did you sing that tune?

LB: Oh no and there is a backstory here. I was touring with Elevation promoting our first album (Mystery, Sunnyside Records 2013) and we ended up the tour in a small city in Transylvania. The promoter took us to dinner after the concert. His daughter encouraged him to sing something for us. And all these amazing old Transylvanian folk songs came out through his beautiful voice and singing. So we found out he is an amazing singer of traditional Transylvanian folk music. He never pursued a career or anything like this but he has a stunning voice and concept and always researched the ancient songbook in villages through the country.

The moment he started singing both Abraham and John had tears in their eyes. Abraham said: "This reminds me to Belize where I'm from. Lush – as he calls me – we have to do something with him." So I asked him to record several a cappella old Transylvanian folk songs, doinas, wedding songs and so on to send it to me to NY where we were going in the studio for our next Elevation album. We arranged these songs in the studio - I arranged the album opening song and a wedding song. John arranged a burning version of the same wedding song. The singer is Gavril Tarmure and he's also an amazing person and he founded this organization Bistrita Concert Society where they produce a lot of concerts, classical and Jazz. But at the same time he has this passion for singing ancient beautiful Transylvanian folk songs.

Going back to composing. May I ask you about the major influences e.g. books, films, pictures, images?

LB: There are many ways to compose and each one does it differently but it also depends on what you are composing for. It is one thing to compose for a small band or for a larger orchestra, for something more classical orientated you know. It depends. A lot of times I have an image in my mind, it's almost cinematic, and then you just go from there.

Do you regard the way you are performing as a pianist lyrically and story telling?

LB: I would like to think its more about story telling. Every music has to tell a story and I think at some points my music is also lyrical.

When you perform with Mat Maneri do you take the role of the bass player and the drummer as well? By asking this question I have “Monastery” in mind. To me there is a strong bass line instead of a soprano line and it seems very rhythmical.

LB: In this particular duo we actually complement each other in many ways. Yes, sometimes you get the impression the piano takes the role of the drums or the bass but we make this music in one breath. We have a special chemistry and the music I think illustrates this. Sometimes you do not need bass or you do not need drums in order to have time present. That is the reason why this duo works for so well and it's been around for some years. We toured all over the States and Europe. Everywhere we play somehow we connect with people. It is strange because we do not play the most accessible music. We found a way that our chemistry functions musically. So you don't feel the need to have a bass or a drums - it is about story telling and hopefully about touching other people with our music.

Is “Travelin' With Ra” a sort of homage for Sun Ra?

LB: Yes, it is a composition I wrote for Sun Ra. Sun Ra was and is still a big influence on me. I love all of his output but especially the stuff from the Chicago period, the early stuff, but also some of the later stuff you know like “Mayan Temples” or the Italian Horo records in quartet with no bass. Sun Ra was also an influence on me with his solo piano playing - I'm thinking of “Monorails & Satellites'! And also the way he looked at music and live - a special dude for sure.

Thank you very much for talking with me.

Interview and photos: ferdinand dupuis-panther

Informations

Lucian Ban

http://www.lucianban.com/

Other

In case you LIKE us, please click here:

Foto © Leentje Arnouts

"WAGON JAZZ"

cycle d’interviews réalisées

par Georges Tonla Briquet

our partners:

Silvère Mansis

(10.9.1944 - 22.4.2018)

foto © Dirck Brysse

Rik Bevernage

(19.4.1954 - 6.3.2018)

foto © Stefe Jiroflée

Philippe Schoonbrood

(24.5.1957-30.5.2020)

foto © Dominique Houcmant

Claude Loxhay

(18/02/1947 – 02/11/2023)

foto © Marie Gilon

Special thanks to our photographers:

Petra Beckers

Ron Beenen

Annie Boedt

Klaas Boelen

Henning Bolte

Serge Braem

Cedric Craps

Christian Deblanc

Philippe De Cleen

Paul De Cloedt

Cindy De Kuyper

Koen Deleu

Ferdinand Dupuis-Panther

Anne Fishburn

Federico Garcia

Robert Hansenne

Serge Heimlich

Dominique Houcmant

Stefe Jiroflée

Herman Klaassen

Philippe Klein

Jos L. Knaepen

Tom Leentjes

Hugo Lefèvre

Jacky Lepage

Olivier Lestoquoit

Eric Malfait

Simas Martinonis

Nina Contini Melis

Anne Panther

Jean-Jacques Pussiau

Arnold Reyngoudt

Jean Schoubs

Willy Schuyten

Frank Tafuri

Jean-Pierre Tillaert

Tom Vanbesien

Jef Vandebroek

Geert Vandepoele

Guy Van de Poel

Cees van de Ven

Donata van de Ven

Harry van Kesteren

Geert Vanoverschelde

Roger Vantilt

Patrick Van Vlerken

Marie-Anne Ver Eecke

Karine Vergauwen

Frank Verlinden

Jan Vernieuwe

Anders Vranken

Didier Wagner

and to our writers:

Mischa Andriessen

Robin Arends

Marleen Arnouts

Werner Barth

José Bedeur

Henning Bolte

Erik Carrette

Danny De Bock

Denis Desassis

Pierre Dulieu

Ferdinand Dupuis-Panther

Federico Garcia

Paul Godderis

Stephen Godsall

Jean-Pierre Goffin

Claudy Jalet

Bernard Lefèvre

Mathilde Löffler

Claude Loxhay

Ieva Pakalniškytė

Anne Panther

Etienne Payen

Jacques Prouvost

Yves « JB » Tassin

Herman te Loo

Eric Therer

Georges Tonla Briquet

Henri Vandenberghe

Iwein Van Malderen

Jan Van Stichel

Olivier Verhelst