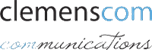

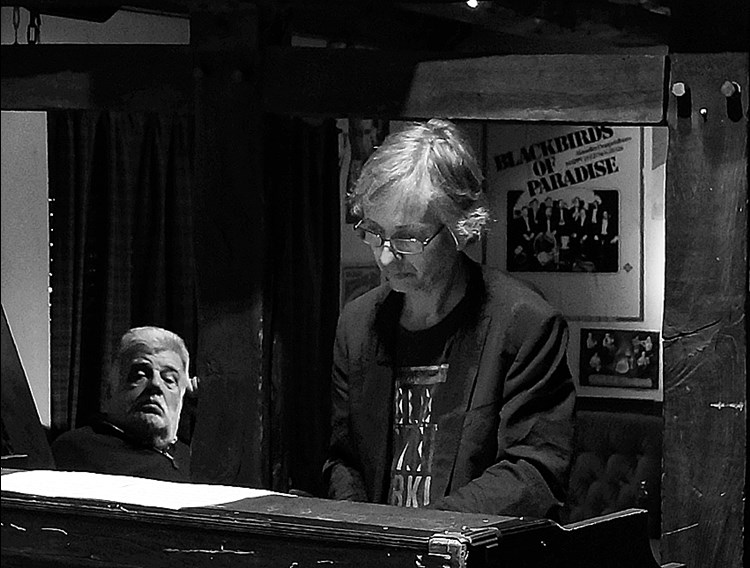

John Hondorp: interview with the Dutch Hammond B3 player

I met John Hondorp before the concert at the Dachtheater Warendorf. He was due to perform with Ansgar Specht & the Hammond Jazz Collective. John Hondorp is employed as a professor at the ArtEZ Conservatory Enschede and Zwolle where he teaches Hammond organ as a major. Apart from keeping a teaching position at the ArtEz conservatory he is as well an appointed teacher for Hammond Organ at the Institut für Musik, Osnabrück (Germany). John Hondorp keeps a Masters Degree in Hammond Organ from the Enschede Conservatory. In the past he toured with jazz artists like Ferdinand Povel, Judy Niemack, Jeanfrançois Prins, Bruno Castellucci and Nippy Noya.

In 2004 he founded the John Hondorp Trio, with guitarist/composer Dominik Korte and drummer Marco Schmitz. After two seasons of playing they recorded the CD “Open Stories” in February 2006 at Organic Music Studio in Obing (Germany). In 2008 John started to cooperate with the German drummer Markus Strothmann. This collaboration grew into a strong duo: Transitions Organ Duo. As a resut their album “No Idea” came out in 2014. It features guest players Frederik Köster and Jeanfrançois Prins, was recorded at “Mühle der Freundschaft” in Bad Iburg and appeared on Unit Records (UTR 4493). We could see Hondorp on stage as well with the Belgian guitarist Jeanfrançois Prins, with the trumpetist Frederik Köster from Cologne or the singer Adrienne West.

How important was music during your upbringing?

JH: It was very strong. From my father's side everybody played music. My father and his siblings were members of an accordeon orchestra - very typical for the Netherlands in the late 30s. They played accordeon when they were 16 until the age of 23 or 24. They all played accordeon or organ. In the 70s organ became very, very popular in Holland, Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Everybody bought an organ. My dad actually traded one of his old accordeons for the first Riha organ that we had in our home. My brother was six years older than I and he was sent to organ lessons and after a couple of months I was just interested, looked over his shoulder what he was doing and copied him. After two years he quit and I continued with playing the organ.

Do you remember the first Jazz tunes?

JH: Well, Jazz wasn't a real topic in my youth. In the 70s the electronic organ was made for popular music, for party music, for organists playing for weddings, singing and playing. Let's put is this way: The organ was a sort of 'Humpda-Humpda' instrument. Jazz came up when I studied and met some great organ players. I studied a lot of stuff written by Jimmy Smith but Oscar Peterson too.

You picked the Hammond B3 as your favourite instrument. Hammond B3 is a very bulky instrument similar to the vibraphone. It is hard to handle and not very sexy. It is difficult to transport. It is demanding in some respect. Why was it your first choice then?

JH: Yes, it is. I came across the large Hammond B3 organ in preparation of my conservatory studies. The Hammond was always considered to be the Ferrari of the electronic organs. Whenever you were really, really able to play organ then you were fit to do the stuff on the Hammond organ. On the Hammond organ you are totally self supporting. There is no automation, no rhythm machine, no pedal sustain if you don't want. It is all pure. All things you do, you do yourself. You have to be able to do it. It was considered and I still consider it as the biggest challenge on the Hammond organ because whatever you hear the organ player do, he does by himself. 100%!

Is there any other challenge to play such an instrument?

JH: The main thing for me is that I don't think so much about the electric circuit in there. I know I can rely on it. It is barely unbreakable and parts which can break I can repair myself because it is so logical. It is not like a failing chip. Then you can throw away the whole motherboard to buy a new one. In a Hammond organ everything can be repaired. That feels very comfortable.

Have you ever played a church organ?

JH: Yes, yes. I do it regularly.

Is there any differences you can see?

JH: Oh, yes. In a way the beauty of the classical organ – I say specifically classical – is that you have to play classical music which means that more or less 95 % of what you are playing is fixed. You play the score. You can only interpret a small part by searching what the composer meant with his composition. That makes you consider far more how to play well and properly than in Jazz. I often tell my students you know maybe we forget how to play the stuff most beautiful because tomorrow we play another note. So there is always another note ahead so we don't bother so much thinking about how to play this one in the most beautiful way. That's the challenge. Playing classical music now and then brings me back to my roots: 2000 people played it before me, how can I play it more beautiful than those 2000. Then you have to be very considerate about every note, on every beat, on every aspect. You have to be very confident you play it in the most beautiful way.

Do you take more the rhythmical or melodic part when playing in a band like Ansgar Specht & the Hammond Jazz Collective?

JH: No, I feel that I am a kind of conductor. I might not be the band leader but I am playing the bass so I should match with the drummer. I am playing a complementary part and consider I am helping the soloist. I play a solo so I take the band where I want to go. Any aspect of the whole tune is at some point in my hands. I have much more overview of the entire composition than when I would only be the 'pianist' of the band that always has the bass player at his side who helps him on his way. The bass player I am myself. In that perspective playing the bass and any other role simultaneously in one body makes you consider and feel the music much more profound than just in one role.

What are the limits of the Hammond B3 in reference to the tunes you can play and the type of Jazz you can perform? The background of my question: For me Hammond B3 is linked to musicians like Jimmy Smith, Brian Auger, Keith Emerson, Jack McDuff, Billy Preston and Joey DeFrancesco.

JH: No, actually I don't think so but the range of organ players you named are, let's put it this way, Blues rooted. If you take the generation of organ players like Larry Goldings that's a different school. It is a school that comes from a Jazz pianist and translating the knowledge of a Jazz pianist to the organ which makes it a totally different instrument, a totally different approach, a totally different style of music. As long as you can change your way of playing and adept to the style you want to play, you can play any style.

Standards and the Great American Songbook are quite relevant for Jazz musicians until today. You will play tonight those standard tunes Ansgar Specht selected for his last album. How important are those tunes for you?

JH: If you put it total unromantically: It was his record and his tunes he selected. I was hired to play on the trio. I liked it and he wanted me to play with him for a long time already. Finally I made time and we did it. We recorded the album and it was his choice of tunes, his concept of favourite songs. We found out that in that repertoire we fit very well together. If you read the reports about this album it made Ansgar a more open, mature and relaxed player playing these tunes in this setting. So actually we are going on a musical journey that seems to fit the three of us very well. Meanwhile we are thinking about our next possible steps without throwing away that what we already have. I think there is nothing wrong with playing within the tradition of the Great American Songbook. It is for a good reason it is called the Great American Songbook. Everybody still wants to hear the symphonies of Beethoven after years. So why should we throw away the American Songbook after 60.

I wonder what type of tunes you would pick for your own band then?

JH: Modern traditional I would call it, the things Larry Goldings composed for instance. The basics are harmonic progressions that lead and push you through a song. The changes you use are more modern than in the Great American Songbook. It is American Songbook 2.0. It is about taking the harmonic basics a step further. But it's not that I am a Free Jazzer. I can't grasp that enough to be leading as an organ player in that kind of setting. My music is gonna have some harmonic roots, tunes built on harmonic ideas.

Could you fancy playing tunes by Coltrane, Monk and Parker?

JH: Yes and no. You asked me what the limitations are in playing the organ. The limitations are that I play two roles all the time. That means I never ever can be so virtuoso with my solo as an organ player in trio setting as just playing an organ or a piano with a bassist next to me. In the latter situation I have nothing else to consider than playing a beautiful, possibly complex and virtuoso solo. Now I am playing 2-part counterpoint with simultaneous basslines and solos. That is doing two things at the same time. It brings down the level of complexity I can play simultaneously but it forces me to cinsider how to play this “easier” stuff the most beautiful way. Make a strength out of your limitations!

But Parker? I have to confess I did not study Bebop enough. I am not the Bebop player. It is too fast and it's changing too fast for me. I should study for two or three years but I am lazy and apparently people like what I am doing now. Why should I do everything? I leave that to Joey DeFrancesco. He studied it so well that he even can't show it slowly. I saw an instruction video and an interview. He was asked to do it again slowly and he was doing it like 'Wuwuwuwu' (racing up and down the keyboard). He tried to show it slowly three times but he could not do it. It's an automation in his motoric skills. Great! I don’t have that. So I am focused on something else.

What is the focus?

JH: I feel I am an European organ player. That means in comparison to some others I have skills to play longer melodic lines, keep tension for a longer period. I grew up with classical music and the long lines of Beethoven's symphonies and the great, great 9th symphony of Dvořák named 'The New World”. It's beautiful stuff which takes 20 minutes to develop and feeling that tension over 20 minutes makes me patient in lines. I think I have something beautiful to say in my melodic lines and the length of my phrasing.

Do you see a rift and drift between the concept of Jazz in the States and in Europe?

JH: If you acknowledge that American people play Jazz differently because it is their native language they grew up with than we play Jazz differently or could play it differently because we grew up with a different type of music. The last time I visited the USA (2004) I travelled to Boston and New York City. What was a siren of a fire truck in Boston when I visited, was a car alarm in New York City. It was the same sound. The proportions were different. You want to be heard in NY City, be louder and more energetic. There are so many people, there is so much going on. So in my opinion New York players are influenced by the energy and the hum and the buzz in their city. I have the feeling that I was influenced by the long lines of a European classical symphony orchestra. And in that way players from both backgrounds express themselves from their own roots. Is one or the other better? No, being loyal to your roots just makes your statement more credible and convincing, whichever it may be.

Thanks for talking with you.

Interview and photos: © ferdinand dupuis-panther

Informations

John Hondorp

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Hondorp

https://www.facebook.com/john.hondorp?fref=ts

http://transitionsjazz.com/

CD reviews

http://www.jazzhalo.be/reviews/cd-reviews/a/ansgar-specht-some-favourite-songs/

http://www.jazzhalo.be/reviews/cd-reviews/t/transitions-organ-duo-no-idea/

Other

In case you LIKE us, please click here:

Foto © Leentje Arnouts

"WAGON JAZZ"

cycle d’interviews réalisées

par Georges Tonla Briquet

our partners:

Silvère Mansis

(10.9.1944 - 22.4.2018)

foto © Dirck Brysse

Rik Bevernage

(19.4.1954 - 6.3.2018)

foto © Stefe Jiroflée

Philippe Schoonbrood

(24.5.1957-30.5.2020)

foto © Dominique Houcmant

Claude Loxhay

(18/02/1947 – 02/11/2023)

foto © Marie Gilon

Special thanks to our photographers:

Petra Beckers

Ron Beenen

Annie Boedt

Klaas Boelen

Henning Bolte

Serge Braem

Cedric Craps

Christian Deblanc

Philippe De Cleen

Paul De Cloedt

Cindy De Kuyper

Koen Deleu

Ferdinand Dupuis-Panther

Anne Fishburn

Federico Garcia

Robert Hansenne

Serge Heimlich

Dominique Houcmant

Stefe Jiroflée

Herman Klaassen

Philippe Klein

Jos L. Knaepen

Tom Leentjes

Hugo Lefèvre

Jacky Lepage

Olivier Lestoquoit

Eric Malfait

Simas Martinonis

Nina Contini Melis

Anne Panther

Jean-Jacques Pussiau

Arnold Reyngoudt

Jean Schoubs

Willy Schuyten

Frank Tafuri

Jean-Pierre Tillaert

Tom Vanbesien

Jef Vandebroek

Geert Vandepoele

Guy Van de Poel

Cees van de Ven

Donata van de Ven

Harry van Kesteren

Geert Vanoverschelde

Roger Vantilt

Patrick Van Vlerken

Marie-Anne Ver Eecke

Karine Vergauwen

Frank Verlinden

Jan Vernieuwe

Anders Vranken

Didier Wagner

and to our writers:

Mischa Andriessen

Robin Arends

Marleen Arnouts

Werner Barth

José Bedeur

Henning Bolte

Erik Carrette

Danny De Bock

Denis Desassis

Pierre Dulieu

Ferdinand Dupuis-Panther

Federico Garcia

Paul Godderis

Stephen Godsall

Jean-Pierre Goffin

Claudy Jalet

Bernard Lefèvre

Mathilde Löffler

Claude Loxhay

Ieva Pakalniškytė

Anne Panther

Etienne Payen

Jacques Prouvost

Yves « JB » Tassin

Herman te Loo

Eric Therer

Georges Tonla Briquet

Henri Vandenberghe

Iwein Van Malderen

Jan Van Stichel

Olivier Verhelst